Pantau Gambut Goes to The 2nd Asia Parks Congress

By Agiel Prakoso

Does Indonesia Still Deserve to be Called an Agricultural Country?

This skepticism stems from the government’s tendency to commercialize every inch of our land rather than fostering meaningful interactions between the people and the land. Farmers are often neglected, struggling not only to own their own land but even to cultivate others' land. This abundant resource has unfortunately also attracted the greed of capitalists and the ruling elite.

The government's backward thinking has influenced the interpretation of what it means to be an agrarian country. Rather than being seen as a holistic connection between people and land, the term has been reduced to merely describing a land rich in natural resources. In reality, understanding the concept of an agrarian nation—one that is prosperous and self-sustaining—is far more complex.

Unpacking the Meaning of Agrarian and Its Implications

The term "agrarian" can be traced back through many linguistic roots. In Sanskrit, the word "ajrah" or "agras" refers to plains. Similarly, in Greek, "agros" means a plot of land. However, it is the Latin term "ager," meaning territory, district, or domain, that offers deeper insights into the concept of agrarianism.

The Latin word "ager" has an adjective form, "agrarius" (also seen as "agrariae" or "agrarium"), which refers to matters related to land or landed property, especially farmland. This suggests that agrarianism involves more than just land or plains—it refers to the unification of territory that forms the basis for a community's livelihood.

This broader definition aligns with Indonesia’s Basic Agrarian Law (UUPA) No. 5 of 1960. While the law doesn’t explicitly define the term "agrarian," it governs the relationship between people and the objects encompassed by agrarianism. According to Article 1, Paragraph (2), UUPA covers the entire earth, water, and airspace, including the natural resources contained within, within the territory of Indonesia.

Articles 6 and 7 further state that all land rights carry a social function, and excessive land ownership is prohibited. These provisions make it clear that UUPA not only regulates agrarian objects but also governs the social and power relations that arise from the natural landscape and the surrounding cultural and social structures.

The Romanticism of an Agrarian Nation: Colonial Tactics of Land Exploitation

The term "agrarian nation" in Indonesia finds its roots in the economic exploitation of agrarian sectors during the colonial period under the Dutch East Indies, particularly through the cultivation system (cultuurstelsel). Lailatusysyukriah (2015), in her analysis titled Indonesia and the Concept of an Agrarian Nation, notes the doctrinalization that agriculture was an inseparable part of the daily subsistence of Indonesian society.

At that time, society was not seen as separate from the agricultural sector, even though many Indonesians lived in coastal areas and did not rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. This doctrine ultimately confined the colonized population to viewing agriculture as the sole foundation of their economy.

This romanticized notion continued into Indonesia’s post-independence era. During Soekarno’s presidency, the population's dependency on rice as a staple food became increasingly evident, especially when Indonesia imported 500,000 tons of rice from India in 1946. Soekarno declared rice a symbol of prosperity, though long before rice cultivation became widespread, the archipelago had a diverse array of carbohydrate sources like sorghum, millet, and sago.

The apex of agrarian romanticism occurred during Soeharto’s New Order regime. In his early years, Soeharto focused heavily on the agrarian sector through Green Revolution policies. These included programs such as the Varietas Unggul Tahan Wereng (VUTW), the construction of large-scale fertilizer factories, and the promotion of pesticides.

While these policies boosted agricultural production, they left lasting ecological impacts. Many local seed varieties disappeared due to the influx of preferred seed strains, and certain insect species were wiped out by the massive use of pesticides.

Soeharto's focus on rice self-sufficiency became more pronounced with the launch of the One Million Hectare Peatland Development Project (PLG) in Central Kalimantan, aimed at converting 1.45 million hectares of peatland into rice paddies. This program, however, failed disastrously, as peatland is unsuitable for rice cultivation, leading to massive forest and land fires from 1997 to 1998.

Despite these failures, the Jokowi administration has attempted to repeat history through its Food Estate program, again targeting the ex-PLG area.

The government’s disregard for the land's natural characteristics has also sparked social conflicts. In Central Kalimantan, several residents have reported land grabs, carried out without consultation. If they resist, the government withholds assistance such as fertilizers, pesticides, or access to markets, leaving these communities’ livelihoods at risk.

Can Indonesia Still Be Considered an Agrarian Nation?

The country once described as "gemah ripah loh jinawi"(fertile and fruitful) can no longer be accurately labeled an agrarian nation. The conditions surrounding the use of the term "agrarian nation," which emphasizes the agricultural sector, are indeed disheartening. This claim is based on two key factors: food production independence and control over agricultural land.

According to the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), there was a significant increase in rice imports, rising by 165.27%, or 1.1 million tons, from January to May 2024 compared to the same period the previous year. During that period, Indonesia imported a total of 2.2 million tons of rice from Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, India, and Cambodia to meet 11% of domestic food needs. It is disheartening that Indonesia, while still bearing the label of an agrarian nation, must import such a large quantity of rice.

In addition to rice, other commodities experiencing import increases during the same period were wheat, up by 35.31%, and wheat flour, up by 14.43%. Wheat imports are mainly used to meet domestic consumption of wheat-based products, such as cookies and instant noodles.

The rise in food commodity imports is in line with the increase in smallholder farmers—those who own less than 0.5 hectares of land—over the past six decades. BPS recorded 17.24 million smallholder farming households in 2023, up from 14.25 million in 2003 and 5.3 million in 1963.

This growing number of smallholder farmers is closely related to the shrinking of agricultural land, which is increasingly being allocated for large-scale infrastructure projects under the banner of National Strategic Projects (PSN). The extremely limited control these farmers have over agricultural land means they cannot sustain their livelihoods solely through farming. They must sell their crops to buy other food necessities.

This phenomenon is known as depeasantization. The number of peasants or subsistence farmers is steadily declining, replaced by large agricultural corporations. This process is clearly seen in the PSN Food Estate projects currently being promoted in several regions of Indonesia, such as North Sumatra, Central Kalimantan, and Papua. Farmers are forced to grow non-native commodities that do not meet their own needs, such as cassava and rice varieties they do not consume.

Additionally, the average age of farmers continues to rise, exacerbated by the lack of regeneration among younger farmers. BPS data shows that the majority of Indonesia's agricultural enterprises are managed by farmers aged 43–58, or Generation X, who make up 42.39% of the total farming population. Meanwhile, farmers from Generation Z (ages 11–26) have the smallest proportion, at just 2.14%.

This historical trajectory and current phenomenon reveal how the romanticization of an agrarian nation has long been used as a packaging for agricultural projects that not only fail to meet the people’s food needs comprehensively and sovereignly, but also damage the environment and disrupt the traditional food culture that has been passed down through generations.

Reinterpreting the Agrarian Nation

Reinterpreting the concept of an agrarian nation can be reflected in its people's sovereignty over access to food and natural resources. The term "agrarian" should no longer be narrowly defined by agricultural productivity and increased crop yields. A truly agrarian nation should also concern itself with the relationship between people and land, water, air, and all the wealth contained therein. This is the ideal image of an agrarian nation.

To be an agrarian nation means ensuring that no one can dominate land ownership excessively, as envisioned in the Basic Agrarian Law. The government must work to eliminate land ownership inequality, which is still monopolized by a small elite group and corporations today. The land should be redistributed to landless communities through land distribution and redistribution policies aimed at dismantling these inequitable structures.

An agrarian nation must ensure that its people have full sovereignty over food as the basis for their relationship with natural resources. This also means recognizing the diversity of food cultures, including paludiculture (cultivation on wetlands) in peatlands, which has long been overlooked because it is deemed "unproductive."

Most importantly, reinterpreting the agrarian nation also involves ensuring environmental sustainability. In an agrarian nation, there should be no more destructive and extractive projects that harm the environment, including peatland ecosystems, to safeguard food sovereignty for today’s and future generations.

Only when we break away from the narrow paradigm of an agrarian nation can we collectively build the true vision of a national granary. This is not merely about food security but about food sovereignty and the welfare of all. Happy National Farmers' Day.

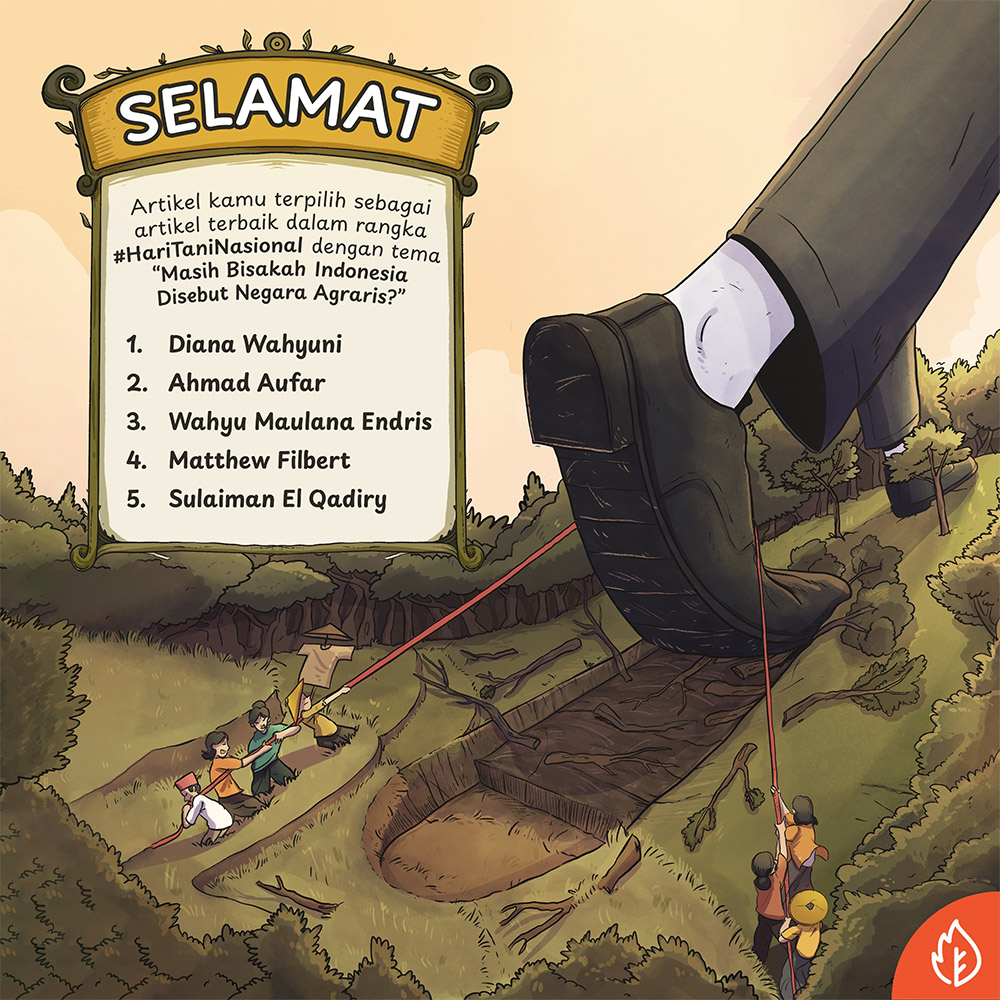

Writing Competition

In celebration of National Farmers' Day, Pantau Gambut is holding an article writing competition on the theme "Is Indonesia Still Worthy of Being Called an Agrarian Nation?" After several rounds of judging, five winning articles have been selected and can be read via the link below.