The Story of Peat on Meranti

By Almo Pradana

Central Kalimantan Food Estate, Your History Today

The development of an agricultural area of this size requires the support of a massive and complex irrigation system. The government has also built a 187 km[1] long Primary Canal to regulate the amount of water entering and leaving by connecting the Barito and Kahayan Rivers. Due to careless calculations, this main canal split the peat dome as deep as 10 meters. With this depth, this peat is included in the category of very deep peat and should be included in a protected area. The water stored in the dome flows out and makes the dome dry. As a result, the peatland area of 876 thousand hectares, which is included in the location of the former peat land development project, has become vulnerable to severe fires every year until now.

Twenty-five years have passed. In 2020, the government was again obsessed with repeating similar projects in the same area. However, instead of repairing and restoring ecosystems that have been damaged, the government has disbursed IDR 1.5 trillion in funds to finance a Food Estate-themed program for 2021 and 2022[2]. This mega project, commanded by the Minister of Defense (Kemhan), is included in one of the 2020-2024 National Strategic Programs. With the inclusion of Food Estate in National Strategic Programs, this program is automatically included in the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN). It can get privileges in preparing annual budgets, permitting space allocation, and legal protection.

With all the facilities it has, the Food Estate has not been able to show good results. Central Kalimantan Province is predicted to become a new national food production center and is ranked as the 20th producer of dry unhusked rice[3]. In 2022, grain production in Central Kalimantan had decreased by 27 thousand tons compared to 2021 in quarters 1 to 3. Its production of 353,865 tons has sunk far below East Java's 9,686,760 tons as the most prominent national grain producer.

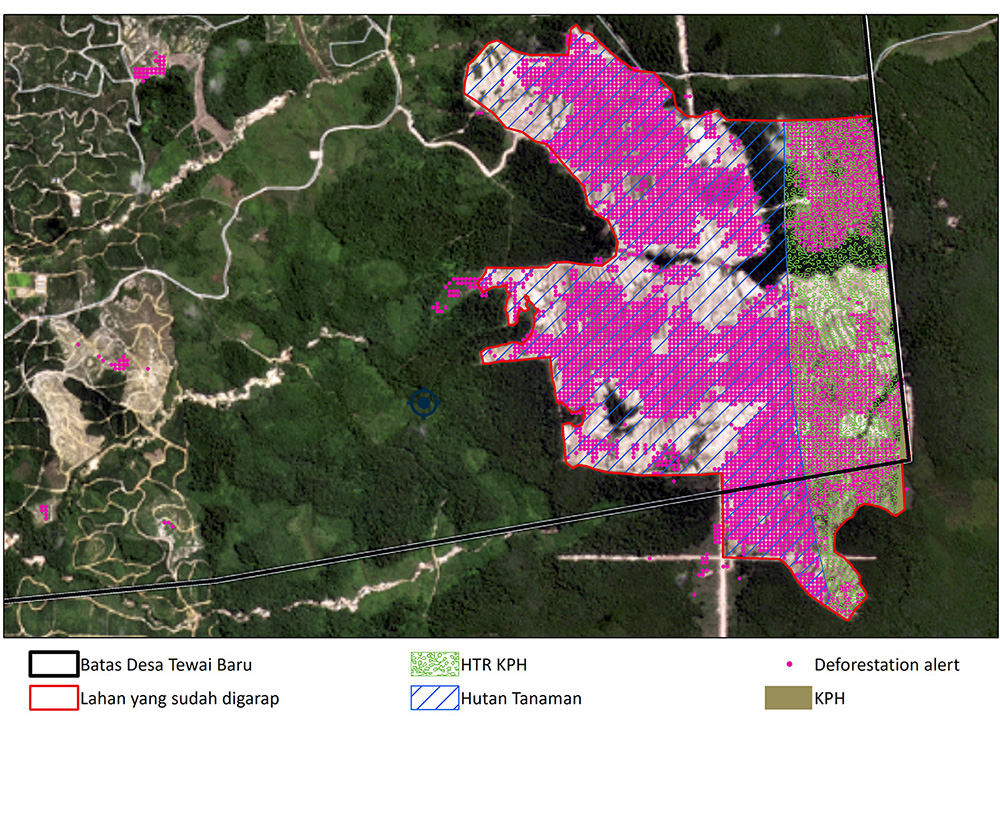

Two years after this premature project began, WALHI Central Kalimantan (Simpul Jaringan Pantau Gambut in Central Kalimantan Province) conducted observations by collecting field information from five villages included in the Food Estate development area, which are Tewai Baru Village, Lamunti Village, Talekung Village Punei, Pilang Village, and Henda Village.

Table of Field Observation Locations

Even though the Food Estate was carried out on land that did not violate regulations, the field observations show the emergence of many socio-cultural problems after implementing the program. For example, the people's land rights are confiscated, and people's livelihood sources are also lost.

Land Ownership Conflicts and Loss of Livelihoods

Conflicts between the government and the community generally occur due to differences in land ownership claims. The community claims that the forest area included in the Food Estate program is a place to depend on for life without disturbing the balance of the ecosystem that has existed for generations. Meanwhile, the government claims that the area used for planting is state-owned land used for the people's prosperity. It sounds noble. Unfortunately, the facts on the field contradict the government's claims.

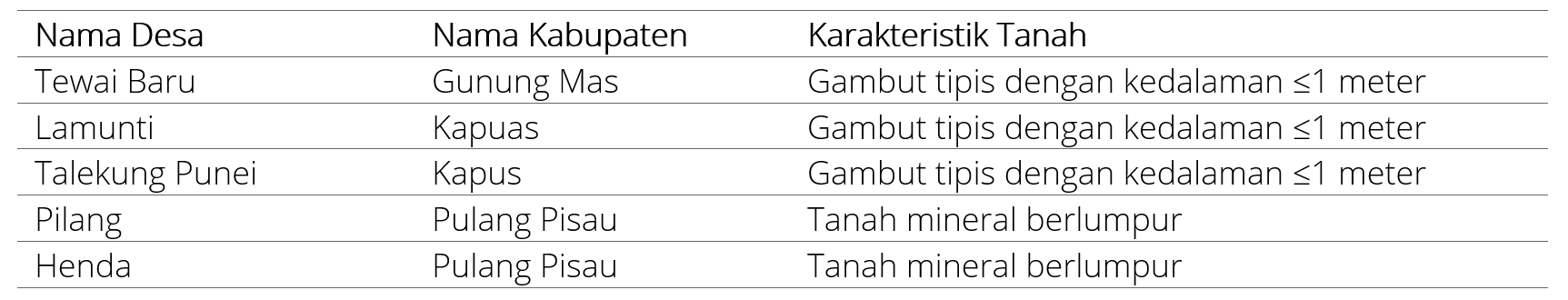

For example, in Tewai Baru Village, the 700 hectares of village land cleared by the Food Estate program makes people lost the source of livelihood for the majority of its residents. Jandra (60), a resident of Tewai Baru Village, said that he and the village community used to use timber and non-timber products from the forests around his village. He added that previously, the forest covered large and dense trees. Therefore, they used to use forest products to meet their daily needs.

After the Food Estate operates, the community is prohibited from taking forest products and carrying out agricultural activities around the project area. Jandra said that when Food Estate entered his village, coordination and socialization regarding the clarity of the land ownership system was minimal. Each coordination is only carried out on a limited basis by inviting several parties such as village officials, heads of farmer groups, and several people acting on behalf of community representatives. Apart from being carried out in a limited manner, this coordination also did not provide clarity regarding community involvement in land management.

Apart from Jandra, Epel Lunce (69) also had an unpleasant experience. "About 3 hectares of my land that was included in the (Food Estate) program was directly worked on unilaterally without any coordination, not even compensation," he explained.

The object area for the Food Estate in Tewai Baru Village is a state forest with a production function. However, based on overlapping with the Indicative Social Forestry Direction Map (PIAPS), the entire area has been allocated as part of the social forestry program since 2019 under the plantation forest scheme. It should be noted that even though the state controls the social forest ownership rights, the management rights are the authority owned by the community in accordance with the Minister of Environment and Forestry Regulation P.11 of 2020 concerning community plantation forests. Unfortunately, there is no involvement in land management, let alone access to former land as the community source of livelihood.

It's different from the story of the Lamunti Village residents, who are considered luckier than the residents of Tewai Baru Village. They are allowed to reject the Food Estate program. Even so, if residents refuse, the government will not promise to assist in the form of seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and market access. Meanwhile, if residents join, they can still manage their private land with the commodities determined by the government. However, this choice is also not without risk since the level of success of planting the commodity they will receive is unknown.

From the phenomena in the two villages, the government only saw an indicative map as a colorful pattern to separate their work areas. At the same time, there is human life that has customs, culture, and human rights that live in it. Apart from seizing people's land, this program makes people lose their sources of livelihood.

The threat of Crop Failure

Another problem in this Food Estate program is crop failure, mainly due to the incompatibility of soil characteristics in Central Kalimantan with the types of plants determined by the government. For example, in Tewai Baru Village, ± 300 hectares of sandy land have been planted with cassava since 2021. Soil with sandy characteristics is not sufficient to support farming efforts[4]. No wonder the residents' cassava harvest did not meet expectations. Apart from being dwarf in size, the resulting cassava root also tastes bitter.

A study mentioned that cassava's bitter taste indicates high cyanide content, which is harmful to the human body[5]. With the cyanide content, this cassava requires a longer processing process to be consumed. Meanwhile, Food Estate planning is meant to cater to large quantities of production, making home-scale processing difficult due to the need for more complex processing equipment. In the end, large-scale corporations will still get benefits from this project.

Crop failure also occurred in Lamunti Village. Residents were instructed to plant rice. However, the characteristics of the thin peat soil in Lamunti Village made the rice yields tested unable to meet the large-scale production targets given by the government. Luckily, the yields are still sufficient to meet the daily needs of the farmers cultivating the Food Estate land. "The type of rice provided by the government does not match the character of our soil, so the rice cannot grow well and causes low yields," said Sio Gatak (63), the head of the farmer group in Lamunti Village.

In addition to the incompatibility of soil characteristics with the specified plants, partial government assistance is also the reason for the frequent failure of the Food Estate program's crops. People who propose development and assistance in the use of irrigation technology do not often receive a response from the government. Irrigation canals are important to help farmers manage the land irrigation system, especially to drain water out when the land is submerged. Drought can cause rice plants to become damaged and even die.

On the other hand, in Henda Village, government assistance in the form of open-close water pipes to regulate the irrigation system on community land was not accompanied by socialization on how to use it. The farmers felt that the donated tools were too sophisticated to use. Therefore, the pipes were not used, and the aid was wasted.

Furthermore, the provision of plant seeds and lime is unsuitable for use because it has expired. In Pilang Village, the government provides seeds and lime when the land is not really ready for planting. While the land is being prepared, the seeds and lime must be stored for quite a long time. In the end, the community had to buy new rice seeds themselves to plant. Lime assistance could not optimally be used because the land cultivation carried out by the military group was not neat. The military group was only toppling growing trees and leaving logs up to the roots of the trees.

The government makes mistakes in many areas. It seems the government does not create a proper study. It reflects how haphazardly the government is conducting studies on implementing Food Estate. Questions about the preparation of the program in Central Kalimantan have also arisen. If the study being carried out is indeed immature, why should the government rush it? Is the past experience from the failure of the Food Estate project not enough to make the government learn and continue to make mistakes? Is this just a consequence of the government's unpreparedness? Is there another agenda hiding behind the Food Estate program?

Ecosystems that have been damaged cannot be returned to the way they were before. At least, it will take a very long time. Development based on the obsession and desire of the authorities cannot be transferred to development based on the real needs of the people. It cannot be known whether this project will continue to be forced, how many more hectares of Central Kalimantan's forest will be destroyed, or how many other local communities will become victims. Central Kalimantan Food Estate can only be history.

Writers : Bayu Herinata and Diani Nafitri Cahyaningrum

Editor : Yoga Dwi Aprillianno

[1] Reposisi PLG Sejuta Hektar Kalteng Sebagai Lahan Pangan

[2] Rincian Anggaran Proyek Food Estate Rp 1,5 Triliun

[3] Digadang Food Estate Dongkrak Produksi, Panen Beras Kalteng Malah Melorot

[4] Tewu, R.W.G., Karamoy, L, Th., and Pioh, D.D. 2016. Study of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties on the Sandy Soil of The Village Noongan District West Langowan. University of Sam Ratulangi

[5] Ndubuisi ND, Chidiebere ACU.2018.Cyanide in Cassava: A Review. Int J Genom Data Min 2018: 118. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-0616.000118