A Look Back at Peatland Protection Commitments on President Jokowi's Birthday

By AdminA Look Back at Peatland Protection Commitments on President Jokowi's Birthday

Take, for example, the National Survey Institute (LSN), which reported a 72.5% satisfaction rate with Jokowi's performance among respondents. Or the Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI), which mentioned an 82% satisfaction rate in April 2023. Reflecting on these various surveys, it's fair to acknowledge that President Jokowi and other executive agencies have indeed introduced populist policies that have had instant impacts on society. One such example is the issuance of Presidential Regulation No. 86 of 2018 on Agrarian Reform and Social Forestry.

The President introduced this regulation based on long-standing conflicts between communities, the government, and concession holders for plantation, industrial timber estate (HTI), and mining permits that were not previously regulated. This program was also included in the Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJM) for 2015–2019 as an effort to address issues related to the slow distribution and access to forest resource assets.

The program also aimed to resolve forest ownership conflicts, ultimately enhancing the well-being of communities living within or around forest areas. In addition to the Agrarian Reform and Social Forestry program, Jokowi also issued Government Regulation (PP) No. 71 of 2014, along with PP No. 57 of 2016, concerning the Protection and Management of Peat Ecosystems. These regulations defined the utilization limits of peatlands, where the water table should not exceed 40 cm from the ground surface. This was a breath of fresh air for environmentalists because it meant peatlands would remain adequately waterlogged throughout the year, preventing them from drying out and becoming susceptible to fires.

In the same year, following the Paris Agreement, Jokowi aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 29% by 2030 through domestic efforts and 41% with international assistance and cooperation. The forestry and land use sector (FOLU) became the primary sector in achieving this goal, to achieve a negative emission of 15 million tons.

To reinforce the commitment to protect peatlands, Jokowi's cabinet, through the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), issued Ministerial Regulation No. 16 of 2017 regarding the Technical Guidelines for Peat Ecosystem Restoration. This regulation reaffirms the critical importance of peat domes in maintaining the function of Peat Hydrological Units (KHG). It defines and regulates that peat domes located within concessions and not yet cultivated must be preserved as protective ecosystems. In other words, any form of extraction activities conducted in these areas is prohibited.

This decision sparked conflicts. It's important to note that not all plants growing on peat are endemic species capable of surviving in waterlogged, highly acidic conditions. The root systems of species originating from dry land cannot thrive in the depths of waterlogged peat. For instance, oil palm trees can survive in a pH range of 4–6.5, while the average peat soil has a pH level of 3–4.

As a result, non-endemic plants widely cultivated on peat within plantation concessions face difficulties in survival and may even die. Consequently, landowners are compelled to create canals to drain the peat, especially in deep peat planting areas. Land areas that operate on peat domes are also prohibited from replanting after harvesting because planting within protected areas is granted only one planting cycle of tolerance. They are also obliged to restore the protective function of the peat dome they have utilized.

A Change of Course

Concerns have arisen among extractive industry players about investing capital. This uncertainty stems from the licensing issues they face when their production areas overlap with restricted peatland ecosystems. Investment progress is hindered by the outcry from concession permit holders, eventually prompting Jokowi to change his course. Restoring peatland ecosystems is no longer a priority; safeguarding the investment climate is considered more crucial.

The winds have also shifted direction as peatland ecosystems have become attractive commodities for exploitation when the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) issued Ministerial Regulation No. 10 of 2019 regarding the Determination, Designation, and Management of Peak Peat Domes Based on KHG. Peat domes, which were previously restricted areas, have been reorganized to facilitate industrial activities in agriculture and forestry, especially for companies struggling with multiple peat domes within their jurisdiction.

Unique circumstances arose when PP No. 57 of 2016 was still in effect when Ministerial Regulation No. 10 of 2019 was enacted. Peat dome cultivation standards doubled. PP No. 57 of 2016, Article 9, Paragraph 4, stipulates that peat with a depth of three meters or more should be designated for protection. However, Article 7 of Ministerial Regulation No. 10 of 2019 states that exploited peat dome peaks can continue to be utilized if at least 30% of the area contains peat domes within the entire KHG area. Consequently, entrepreneurs are permitted to use peatlands with certain conditions. Nevertheless, it's a fact that draining peat domes for agriculture will impact the water supply in the surrounding peatland areas. The peatland expanse around peat domes will lose water support, become dry, and prone to fires.

The government became even more open about exploiting peatland ecosystems when Jokowi ratified Government Regulation in Lieu of Law (Perppu) No. 2 of 2022 concerning Job Creation (UUCK) – a regulation that shouldn't have been ratified due to a lack of urgency in its issuance. According to Pantau Gambut's report, 857 oil palm plantations, covering 3.4 million hectares, have been actively operating within forest areas without valid forestry permits. The ease of doing business in forest areas, including peatlands, was facilitated through two schemes outlined in Articles 110A and 110B. Scheme 110A stipulates that plantations that previously only had permits from local governments before the UUCK came into effect only need to pay administrative fees to the KLHK as compensation for legitimizing their businesses. Meanwhile, Scheme 110B opens the door for illegal plantations to obtain business permits by simply paying administrative fines. Clearly, plantations should not be operating in forest areas.

In the above paragraph, it appears to corner Jokowi for his role as a president who should be able to please as many parties as possible. In reality, Jokowi's role as a role model for citizens deserves criticism. In March 2017, the Palangkaraya District Court issued a guilty verdict against Jokowi, along with a series of ministries and local governments, in response to a lawsuit from the public due to government negligence resulting in the severe forest and land fires in Central Kalimantan in 2015. Five years after that verdict, Jokowi escaped legal entanglement after submitting a Request for Judicial Review (PK) to the Supreme Court (MA) in August 2022, which was granted in November 2022. The defendants were only obligated to enact several regulations to address and prevent forest fires in Kalimantan. However, the presidential office, through Moeldoko as the Chief of Presidential Staff, defended Jokowi by claiming that he had taken tactical measures in the field to resolve the forest fire issue. He stated that forest and land fires had decreased by 98%. This statement served as a shield used by the presidential office to protect Jokowi because, in reality, the vulnerability to forest and land fires spread again a few months later in 2023.

Amidst the Haze

It's crucial to emphasize that damaged peatlands worsen the impact of forest and land fires. Over the past decade, history has witnessed at least two significant forest and land fire incidents in 2015 and 2019, scorching millions of hectares of peatlands. Pantau Gambut's analysis revealed that the fires in 2015 encompassed 2.6 million hectares, and in 2019, approximately 1.6 million hectares burned, with nearly 29% of these fires occurring on peatlands. Despite the smaller area of peatland fires compared to non-peatland areas, these peatland fires are concerning due to their immense carbon storage. If peatlands are drained and degraded, an average of 55 metric tons of CO2 will be released annually. To put this in perspective, it's equivalent to burning over six thousand gallons of gasoline each year.

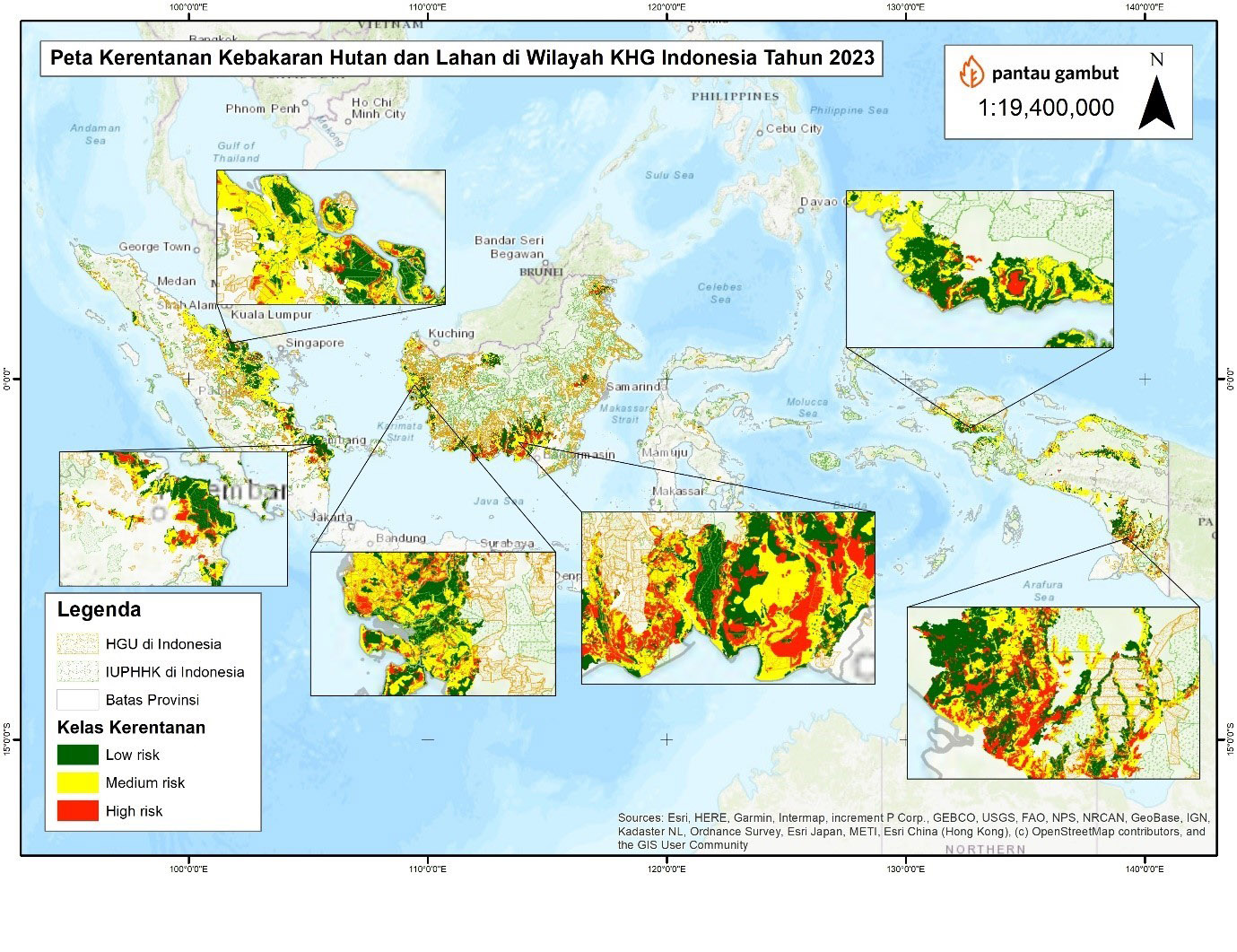

In 2023, Pantau Gambut documented that 16.4 million hectares of Peatland Hydrological Units (KHG) were vulnerable to fires, with over half of this total area falling within concession areas and their buffer zones. Companies with plantation permits (HGU) and wood forest permits (IUPHHK) dominated these fire-prone areas. Based on their distribution, Central Kalimantan (1.2 million hectares) and South Papua (0.5 million hectares) emerged as two provinces with a high risk of forest and land fires. Besides these two provinces, West Kalimantan and Riau followed as provinces with high-risk areas for forest and land fireswithin KHGs in 2023, each covering approximately 400,000 hectares.

The two provinces in Kalimantan, which consistently face the largest forest and land fire incidents each year, raise concerns about the sustainability of two National Strategic Projects (PSN) in Kalimantan: the new Capital City (IKN) and the National Food Security Program, commonly known as the Food Estate. In addition to preparing the new Capital City (IKN) as a smart forest city, Jokowi must also confront the fact that the IKN's location in Penajam Paser Utara District, East Kalimantan Province, is threatened by the encroaching haze from forest and land fires in its buffer regions.

Nine KHGs spread across the former One Million Hectare Peatland Development (PLG) Project in Central Kalimantan still have the potential to ignite. After over 20 years, the One Million Hectare Rice Field Project initiated by former President Soeharto has left behind fragmented lands due to canalization, as land restoration has yet to yield results. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) issued Presidential Instruction (Inpres) No. 2 of 2007 on Accelerating Rehabilitation and Revitalization of Peatland Development Areas in Central Kalimantan, and President Jokowi further reinforced efforts to combat forest and land fires through Government Regulation No. 71 of 2014, Article 27, stating that business owners and/or activities utilizing peatland ecosystems that cause peatland ecosystem damage within or outside their operations must undertake mitigation measures as stipulated in their environmental permits. However, according to Pantau Gambut's records, at least 989,000 hectares of former PLG lands still have the potential to burn.

Beyond IKN, a portion of the National Strategic Project (PSN) Food Estate is also being implemented in Kalimantan and Papua. This national strategic program stirred controversy when the Minister of Environment and Forestry issued Regulation No. 24 of 2020 concerning the Allocation of Forest Areas for Food Estate Development. This regulation allowed Food Estate development to take place in production forests and/or protected forest areas. Although this rule was later revoked and replaced with Regulation No. 7 of 2021 concerning Forest Planning, Changes in Forest Area Designation, Changes in Forest Area Function, and Forest Area Use, substantively, not much changed. Article 485 still allows Food Estates to be established in protected forest areas.

Through this Regulation, nearly all areas designated for Food Estate projects in South Papua Province were within forest areas. Four districts – Merauke, Mappi, Boven Digoel, and Yahukimo – were projected to provide 2.6 million hectares of land for the large-scale food program. When the indicative Food Estate location map is overlaid with peat distribution, the Area of Interest for the planned Food Estate in Mappi District intersects with shallow peat (depth of 50–200 cm). Pantau Gambut found that 56% of the indicative Food Estate area in Mappi District falls into the high-risk category for fires

The Food Estate in Central Kalimantan presents even more ecological and socio-economic concerns. During satellite image verification in Pulang Pisau District, Pantau Gambut identified new land use conversion patterns in two villages designated for the Food Estate program – Pilang and Jabiren. These locations, situated in peat swamp-protected forest areas with depths of 2–3 meters, clearly experienced violations because forest clearance and land conversion should not have occurred in these areas. Between 2020 and 2022, Pantau Gambut observed indications of forest cover loss in three Food Estate area districts: Pulang Pisau, Kapuas, and Gunung Mas.

Land use conversion further complicates this Jokowi government program. The Jakarta-centric approach that introduced various new "goods" to Food Estate locations undermines the centuries-old beliefs of local communities. For example, in Tewai Baru Village, Gunung Mas District, 600 hectares of forest were cleared and converted into a Food Estate working area. The previously rich forest, which provided sustenance for the local population, has now become an empty expanse where cassava crops failed to thrive. The villagers, who once coexisted and relied on forest resources for their livelihoods, have been marginalized from their ancestral lands due to restricted access to the project area.

The End of Jokowi's Tenure

There are at least three crucial points that demand attention as Jokowi faces the conclusion of his presidency, due to the substantial tasks remaining.

First, despite Jokowi's commitment to climate issues and peatland restoration, his efforts have often been ambiguous and at odds with other policies. For instance, regulations on peat dome utilization clash with the need to maintain its water supply. The ease of granting operational permits to problematic corporations is another issue. This is especially evident when considering policies related to Food Estates in protected areas. All of these aspects highlight the need for a comprehensive policy evaluation.

Second, the implementation of environmental protection policies, especially regarding peatland ecosystems, has shown weaknesses in law enforcement. Field observations and Pantau Gambut studies indicate that the risk of peat ecosystem damage persists, with occurrences of fires and high vulnerability within concession areas. This underscores the necessity for stronger law enforcement and more effective policies for peatland protection. This includes evaluations of new and existing permits, revoking problematic permits, and law enforcement for concessions that have repeatedly experienced fires.

Lastly, President Jokowi's role as a leader of the nation and as a citizen in dealing with legal issues should not serve as an example. The overturning of guilty verdicts for Jokowi and several officials regarding the 2015 Central Kalimantan haze crisis has created a perception that power can buy justice. Ultimately, Jokowi's commitment to environmental conservation and effective peatland protection has come under significant scrutiny.

In general, there is a need for consistency, coordination, improved law enforcement, and policies that prioritize effective peatland protection. President Jokowi can enhance environmental policies during his remaining time in office by giving more attention to peatland protection, strengthening environmental law enforcement, and reconciling conflicting policies to achieve more robust and sustainable environmental conservation goals.

Happy 62nd birthday, Mr. Jokowi! We wish you all the best sir!