Pantau Gambut Annual Report 2017

By Pantau GambutWhitewashing Illegal Palm Oil Corporation: A Poor Practice in Palm Oil Governance Aggravating Environmental Crimes

The government's inadequate practices in managing the environment are becoming progressively conspicuous. Policies are being devised to legalize a series of illegal activities. This is evident in the agenda to legitimize oil palm plantations that have already been established within a 3.3 million-hectare forest area across Indonesia. It showcases the minimal commitment of the state to protect the environment, combat environmental crimes, eradicate corruption, and prioritize the welfare of its citizens. These policies even shield repeated environmental crimes committed by palm oil plantation companies.

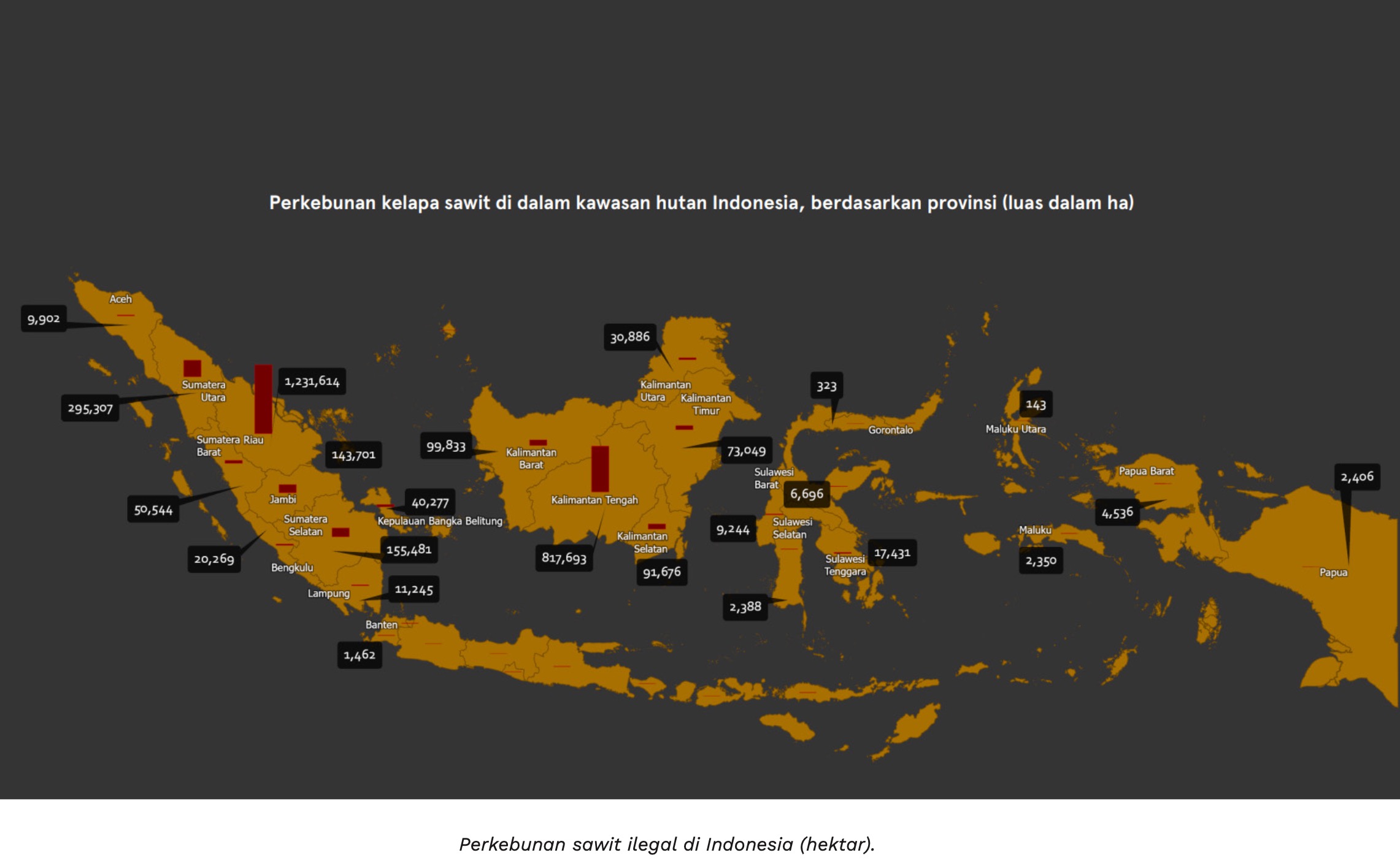

According to Greenpeace and TheTreeMap (2019), there is a total area of approximately 3,118,804 hectares of oil palm plantations established within forest areas in Indonesia. Half of these belong to palm oil plantation companies, with over 600 companies managing more than 10 hectares each within forest areas. Moreover, palm oil is planted on land designated for conservation and protection forests, with respective areas reaching 90,200 hectares and 146,871 hectares. This data also identifies the top 25 RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) member groups based on the total area of palm oil planted within forest areas. The top ten groups planting palm oil within forest areas include Sinar Mas, Wilmar, Musim Mas, Goodhope, Citra Borneo Indah, Genting, Bumitama, Sime Darby, Perkebunan Nusantara, and Rajawali/Eagle High.

"Illegal oil palm plantations have proliferated across various regions, including protected forest areas, due to poor governance by the government, lack of transparency, and weak law enforcement. Instead of addressing these issues, the government is whitewashing illegal palm oil plantations within forest areas. This policy clearly does not serve the environment, indigenous communities, and local populations affected by it. Instead, it is suspected to benefit the palm oil oligarchy entrenched in positions of power," stated Syahrul Fitra, Greenpeace Indonesia's Forest Campaigner.

In an ecological context, the agenda to whitewash illegal palm oil plantations within the Peat Hydrological Units (PHUs) will exacerbate forest and land fires (forest and land fires - karhutla) along with their accompanying ecological impacts. Pantau Gambut (2023) identified that out of a total of 3.3 million hectares slated by the government for whitewashing, approximately 407,267.537 hectares (around 13-14%) are situated within the PHUs. Among these, 72% of oil palm plantations in the PHUs earmarked for whitewashing fall under the medium-risk category for fire susceptibility, while 27% fall under the high-risk category. Furthermore, 91.64% of concession holders obligated to mitigate and restore the damaged peat ecosystems resulting from forest and land fires within their areas have not implemented restoration measures in the field.

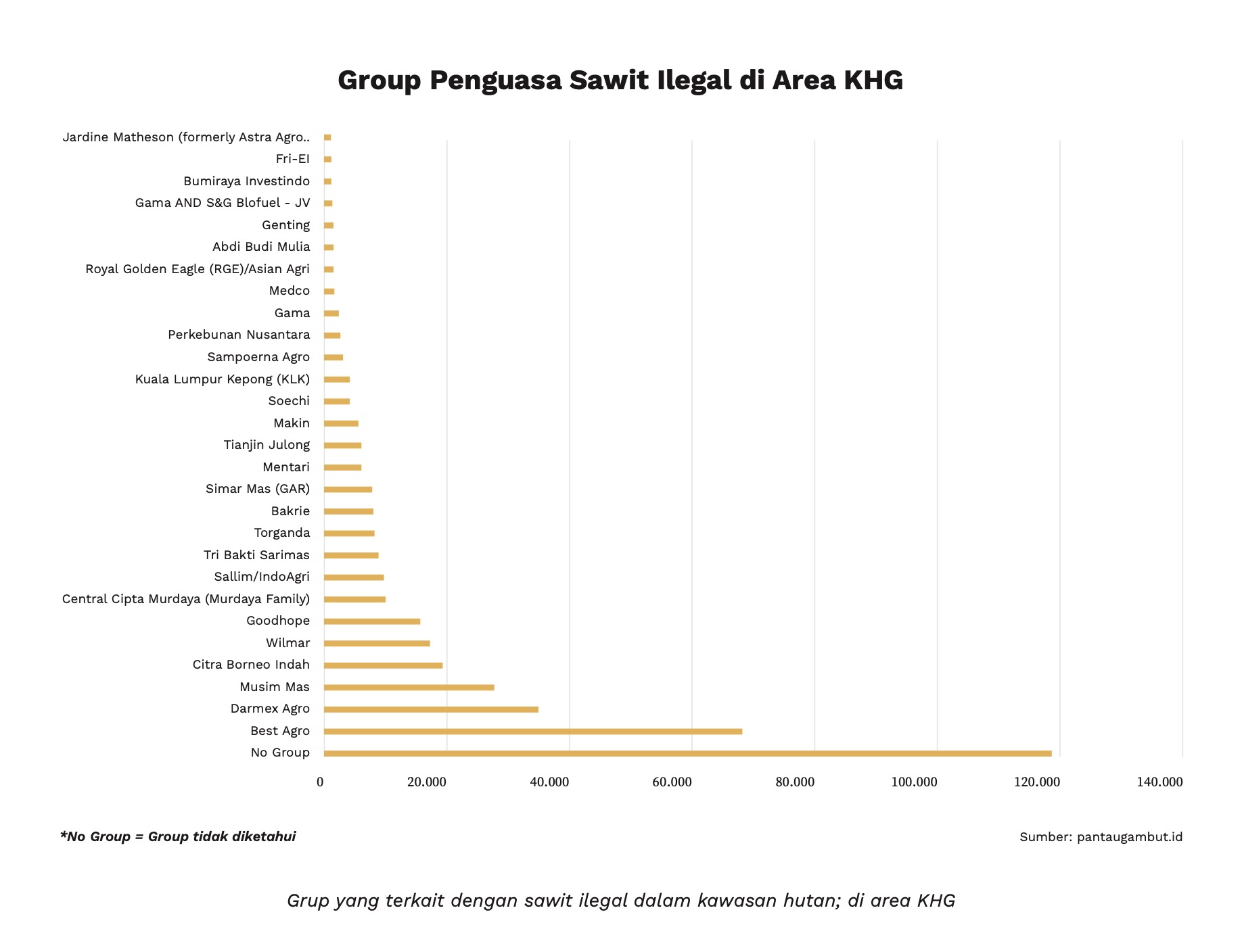

Wahyu Perdana, the Advocacy and Campaign Manager of Pantau Gambut, stated that based on Pantau Gambut's findings, out of the 32 illegal palm oil company entities operating within the PHUs, only 5 companies genuinely operate within peat ecosystems for cultivation purposes, while the remaining 27 companies (84%) operate within peat ecosystems designated for protection. This highlights violations of Article 21 of Government Regulation No. 71 of 2014, in conjunction with Government Regulation No. 57 of 2016 concerning the Protection and Management of Peat Ecosystems. This condition heightens the risk of forest and land fires (karhutla), particularly within peatland ecosystems.

Another issue accompanying these poor practices is related to the ongoing forest and land fires occurring within palm oil plantations. Pantau Gambut processed the burn area data from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) for the years 2015-2020. They found that eleven corporate groups involved in the whitewashing scheme within the PHUs had a history of burnt areas due to forest and land fires from 2015 to 2020. Among these, the corporate group with the largest burnt area was Best Agro Plantation, totaling 3,605,876 hectares, followed by Soechi with a total burnt area of 2,085,382 hectares, and Citra Borneo with a total burnt area of 1,704,521 hectares.

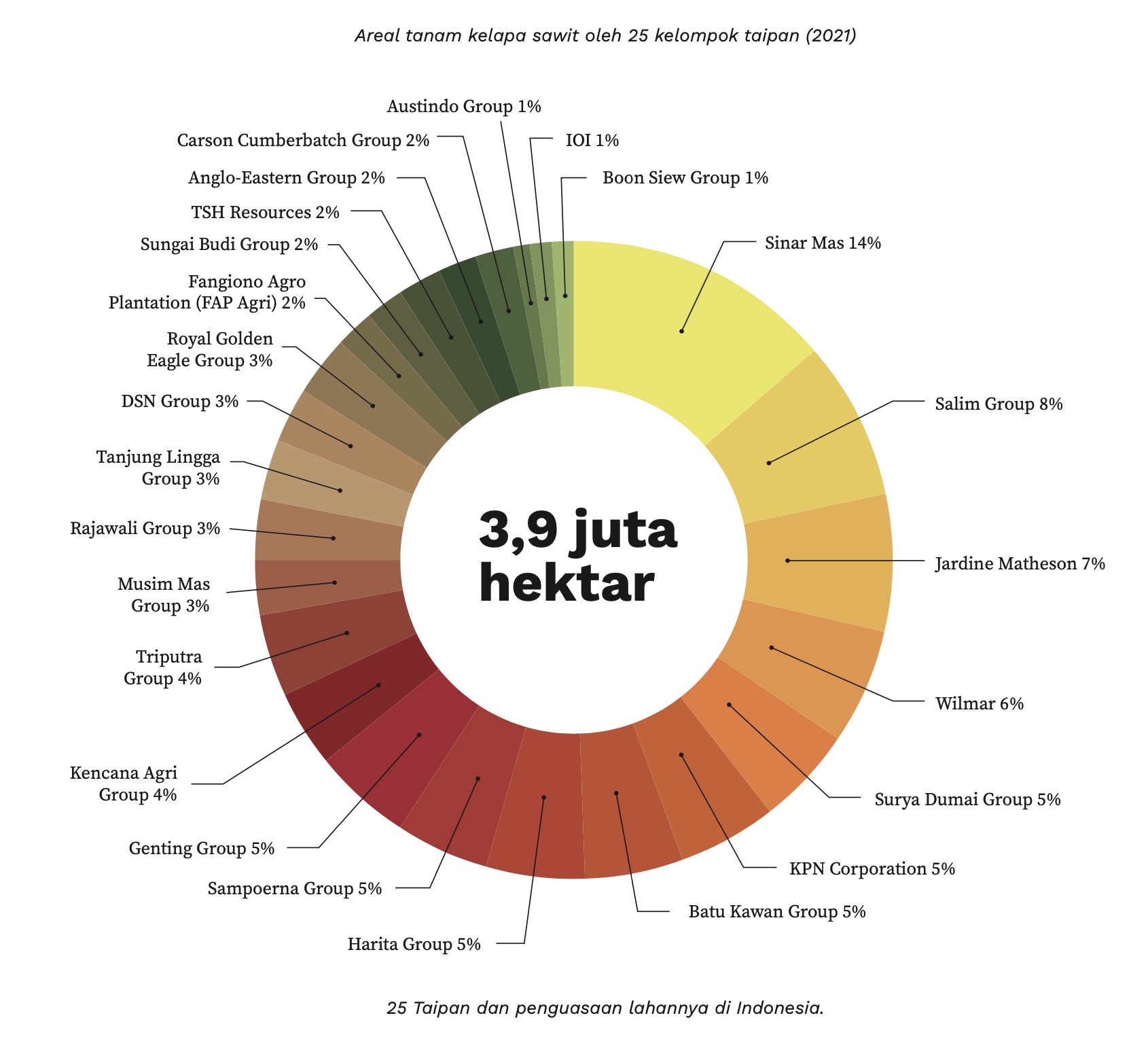

The identified groups associated with illegal palm oil plantations within forest areas are significant players in Indonesia's palm oil industry. TuK INDONESIA (2023) identified 25 major corporate groups controlling a total plantation area of 3.9 million hectares in Indonesia. Data reveals that out of the 3.9 million hectares of oil palm plantations, the majority of land control is by Sinar Mas (14%), Salim (8%), Jardine Matheson (7%), Wilmar (6%), and Surya Dumai Group (5%). These corporate groups receive substantial financial backing from financial institutions. For instance, Sinar Mas obtained corporate loans totaling 17.5 million USD (equivalent to Rp247.9 billion) from Banco de Sabadell and ABN AMRO respectively. Additionally, Bank Central Asia (BCA) and Bank Sinar Mas also provided financial backing to Sinar Mas. Wilmar, on the other hand, received a revolving credit facility of 24.6 million USD (equivalent to Rp348.5 billion) from Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation in 2018, and in subsequent years, continued to receive credit and investment facilities from the same financing institution. Interestingly, even pension fund financing institutions in Malaysia, such as the Employees Provident Fund, financed the Genting Group, benefiting from the whitewashing agenda, with a total of 110.1 million USD in 2022, equivalent to Rp1.7 trillion.

TuK INDONESIA also identified that several palm oil companies listed for whitewashing have repeatedly been involved in environmental crimes related to forest and land fires in Central Kalimantan based on their fire hotspot locations. These companies include: PT Bangun Cipta Mìtra Perkasa (Best Agro); PT Globalindo Agung Lestari (Genting Group); PT Karya Luhur Sejati (Best Agro); PT Rezeki Alam Semesta Raya (Soechi Group); and PT Bangun Cipta Mìtra Perkasa (Best Agro).

Ironically, an agenda purportedly aimed at increasing state revenue has failed to substantiate such claims. TuK INDONESIA's (2023) case study in Central Kalimantan demonstrates that the tax realization from the legal palm oil sector falls far short of its potential. Despite an estimated potential of over Rp6.4 trillion, Central Kalimantan was only able to realize around Rp2.3 trillion in taxes, and this figure encompasses taxes from all sectors. Claims of increased income through an agenda that evidently facilitates ongoing environmental crimes and the breakdown of plantation and forestry governance no longer hold relevance.

"This whitewashing is undoubtedly a form of state crime. It should be a serious concern for financial institutions and imperative to reassess financing for companies proven to have planted oil palm within forest areas, even those involved in environmental crimes (karhutla). The discovery that these palm oil plantation companies operating within forest areas are also members of the RSPO supports our earlier statement that indeed, RSPO certification lacks credibility," remarked Abdul Haris, TuK INDONESIA's Campaigner.