Alert of Forest and Land Fire Vulnerability in 2022

By Oriz Anugerah Putra, Agiel Prakoso dan Iola AbasRiau haze, where does it come from?

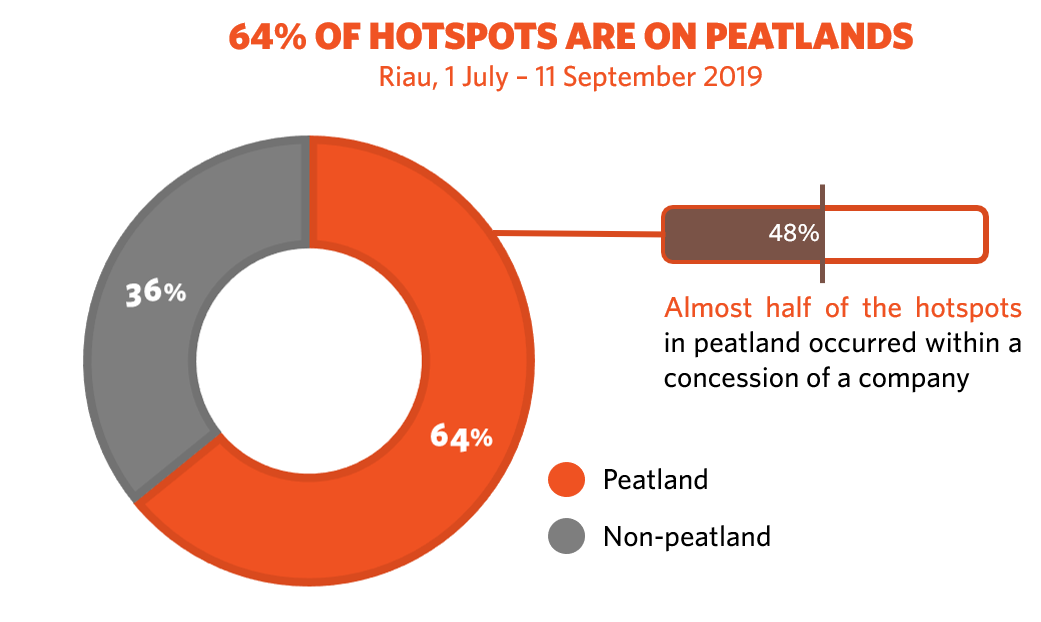

Massive forest and land fires in Riau have caused multi-sectoral losses. Pantau Gambut analysis from 1 July – 11 September 2019 shows that the majority of fires in Riau occurred on peatlands and almost half of them are within concession area. Although historically Riau was the location of forest and land fires in Indonesia for the past 15 years, the annually recurring fires in the concession areas should be a highlight.

Riau sees forest and land fires every year. As a matter of fact, hotspots have been discovered since the beginning of 2019 which should have been estimated as the rainy season. Riau people are forced to return to nostalgic years living with the thick and suffocating haze, similar to the one in 2015.

The engulfing haze not only disturbs the people’s lives, but also affects the air quality, making it hazardous to breathe.

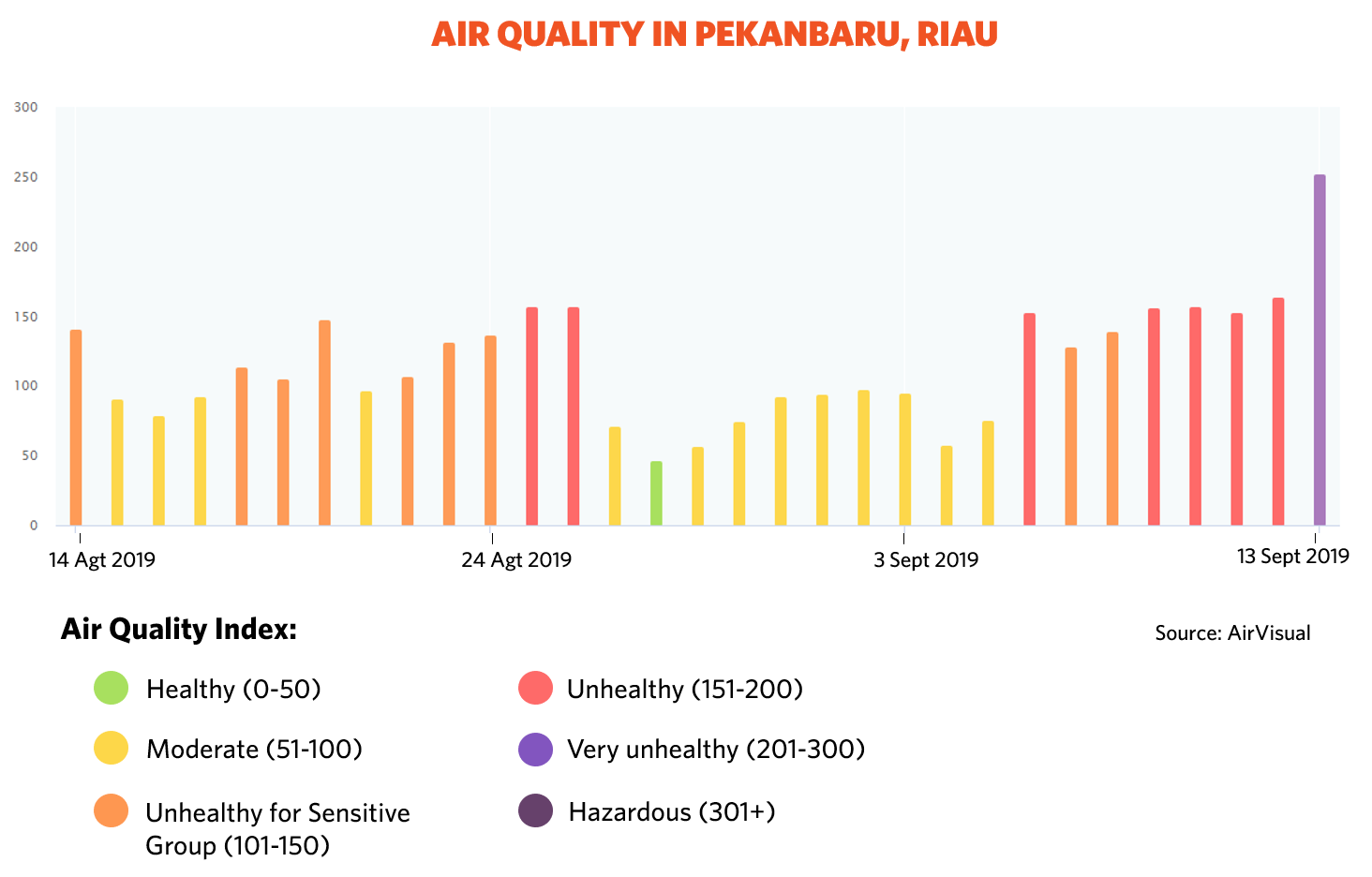

The Air Quality Index shows that Pekanbaru’s air quality from 14 August – 13 September 2019 is at an alarming rate. In fact, as of 13 September 2019, the air quality in Pekanbaru falls into the “Very Unhealthy” category. The haze from the forest and land fires contains hazardous gases and particles such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide, sulphur dioxide and other hazardous compounds. Particulate matters are also carried by the haze, potentially causing health problems for anyone who breathes them.

Yohanes, Head of Riau Health Service, explained that 21,671 people in Riau have been infected with acute respiratory infection (ARI). Pekanbaru has the highest rate of acute respiratory infection compared to other areas in Riau. The number of people suffering from the infection peaked in August 2019 to more than 5,000 people. While forest and land fires actually only occur in several areas of Riau, the engulfing haze is actually carried by the wind to Pekanbaru, disrupting activities in the capital city of Riau.

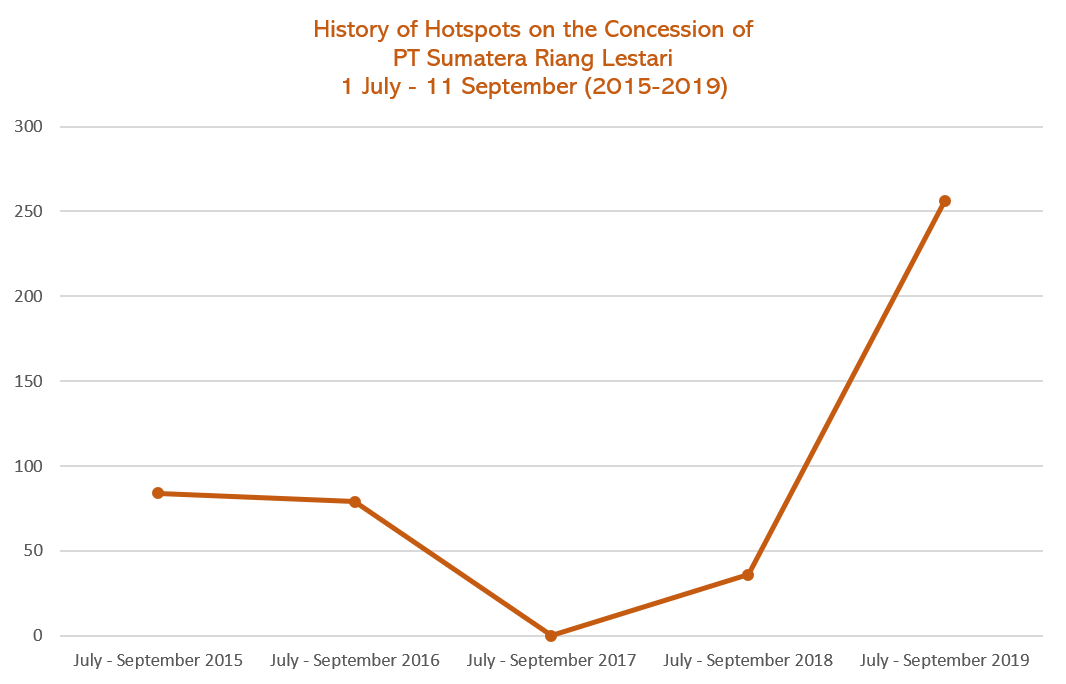

Pantau Gambut’s analysis shows a higher number of hotspots in 2019, compared to 2015 when the severe forest and land fires hit Indonesia during the same period in July – August.

Global Forest Watch’s data shows 21.833 hotspots occurring in Riau from 1 July – 11 September 2019. Sixty-four percent of the hotspots occur on peatlands, while the remaining forty-eight percent occur within licensed cultivation areas. This number is predicted to increase as the long drought continues until November 2019.

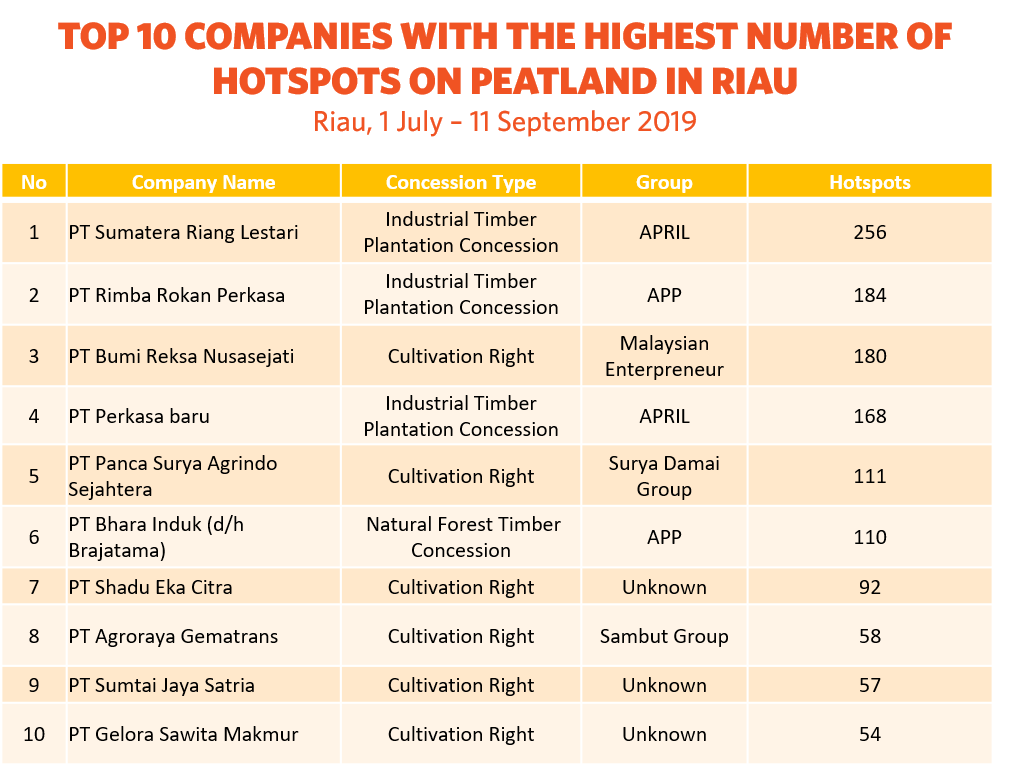

Pantau Gambut analyse concession holders in Riau peatland from 1 July – 11 September 2019. As a result, 10 companies are identified with the most number of hotspots.

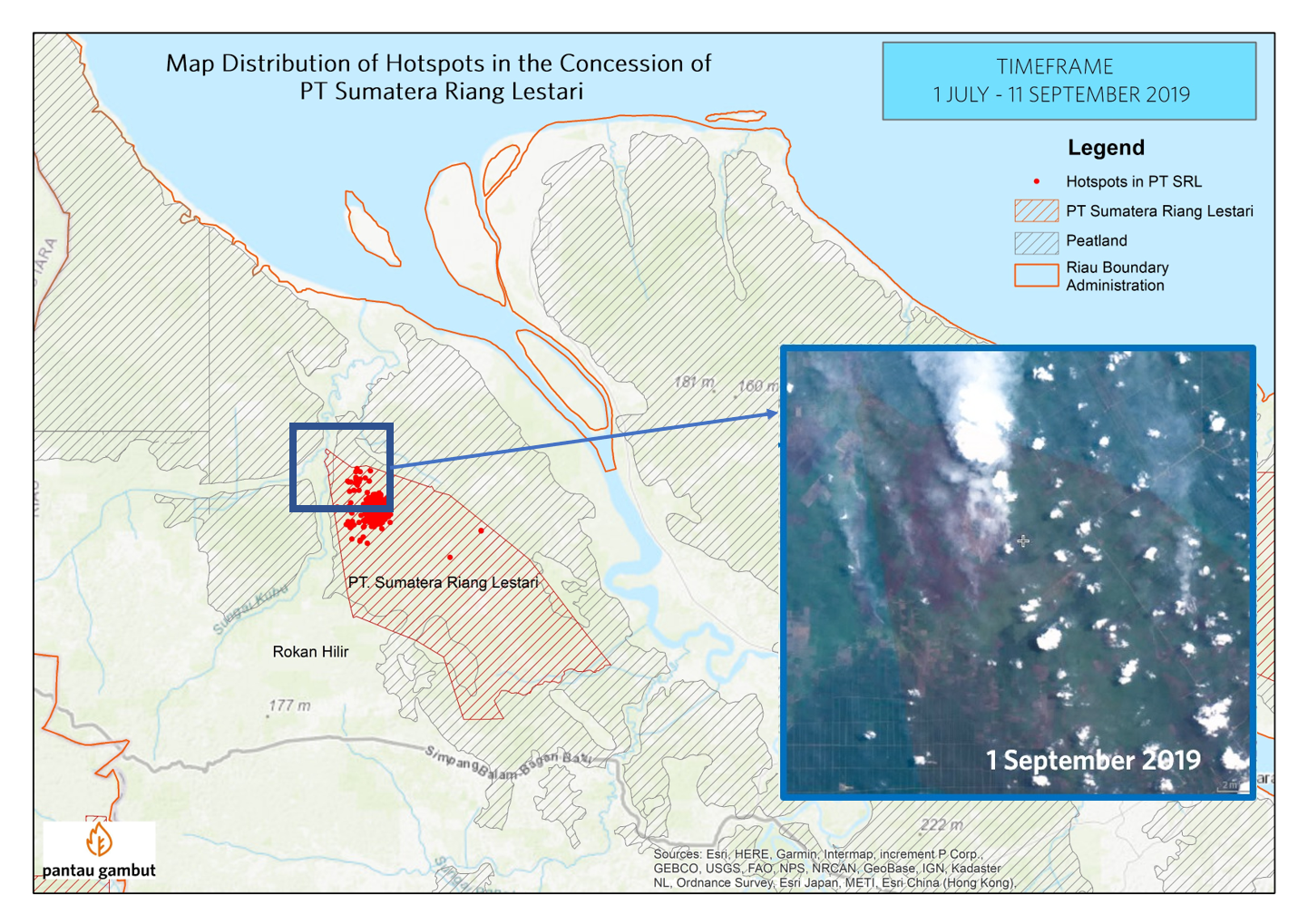

PT Sumatera Riang Lestari (SRL) takes the first place for the highest number of hotspots occurring on its concessions within the 1 July – 11 September, 2019 period. It is time for PT SRL to be closely monitored considering its previous involvement in a forest fire in its concession in 2015.

In 2019, the area of PT SRL is burned once again. Pantau Gambut’s analysis shows more than 250 hotspots caught by the VIIRS sensors during the period of July – September 2019 in the affiliated company of Asia Pacific Resources International Holding Limited (APRIL). This is a steep increase compared to fire trends in the previous years.

Forest and land fires keep reoccurring due to the lack of supervision over the implementation of restoration, especially in concession areas. Limited public access to comprehensive data on the progress of peat restoration on concession areas raises the question whether restoration commitments have actually been realized.

There are at least three laws and regulations referred to by the Forest and Land Fires Task Force (The Indonesian Army (TNI), The National Police (Polri), the Regional Disaster Management Agency (BPBD), Manggala Agni and other relevant elements) in cracking down on perpetrators of forest and land fires. These are Law Number 41 of 1999 concerning Forestry, Law Number 18 of 2004 concerning Plantation and Law Number 32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Guidelines and Management.

More specifically, the Environmental Guidelines and Management Law mentions three law enforcement mechanisms. They are administrative sanctions from written warning to revocation of licenses, civil sanctions from compensation to the obligation to restore burnt areas and criminal sanctions from fines to seizure of profits. Unfortunately, these three legal standards do not seem to have the effect of compliance, especially for large companies and groups that continue to be involved in similar cases every year.

This begs another question on law enforcement in the case of forest and land fire. Are the existing laws neither binding nor effective?

Riau has been included in the peatland restoration priority program, but these fires on peatlands show that restoration efforts have been ineffective as damaged peat requires time to recover. The Field Analysis of Pantau Gambut in restored areas in Riau recommends for all stakeholders to ensure the proper implementation of peat restoration, including in concession areas.