Confronting a Deliberate Food Crisis

By AdminAlert of Forest and Land Fire Vulnerability in 2022

The BMKG also warns that the threat of forest and land fires in 2022 will be higher than in 2021 due to a drier dry season in most parts of Indonesia than in 2021. Even though according to the BMKG there will be no warming sea surface temperature (El Niño) phenomenon in 2022, preparation for the dry season must still be to the priority and awareness of haze disasters during the dry season must continue to be increased, especially in peatlands where fire is difficult to be extinguished when it burnt. Therefore, the government and various related parties, including the public, need to increase their vigilance and preparation in facing the threat of forest and land fires.

History of Forest and Land Fires in Indonesia

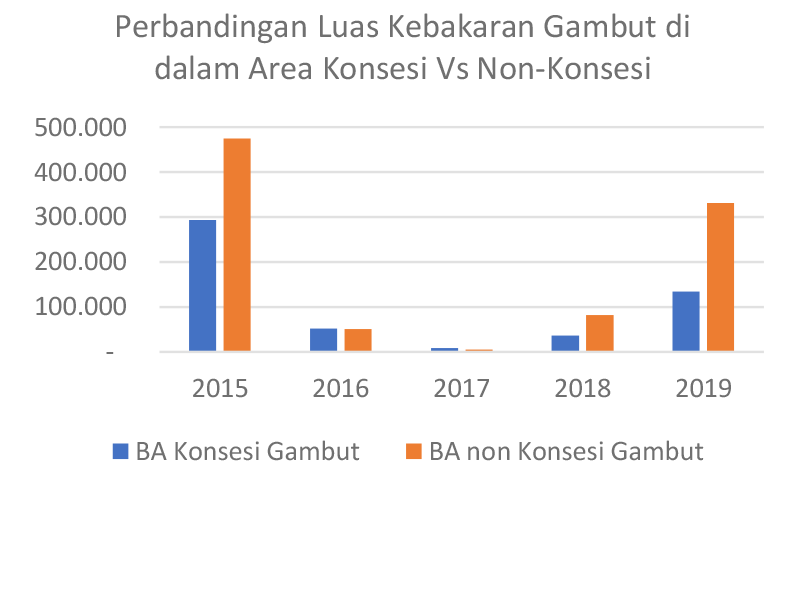

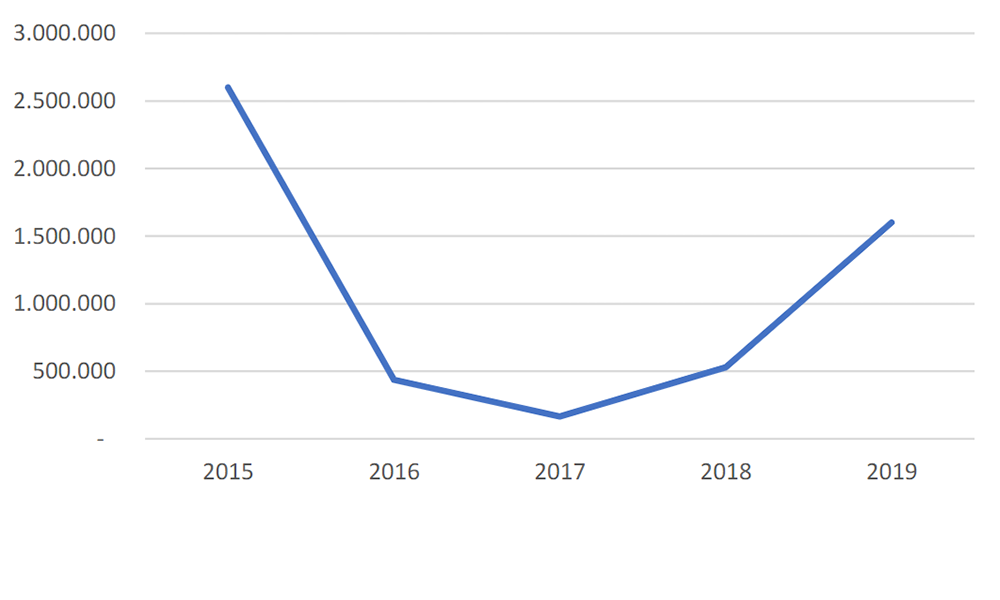

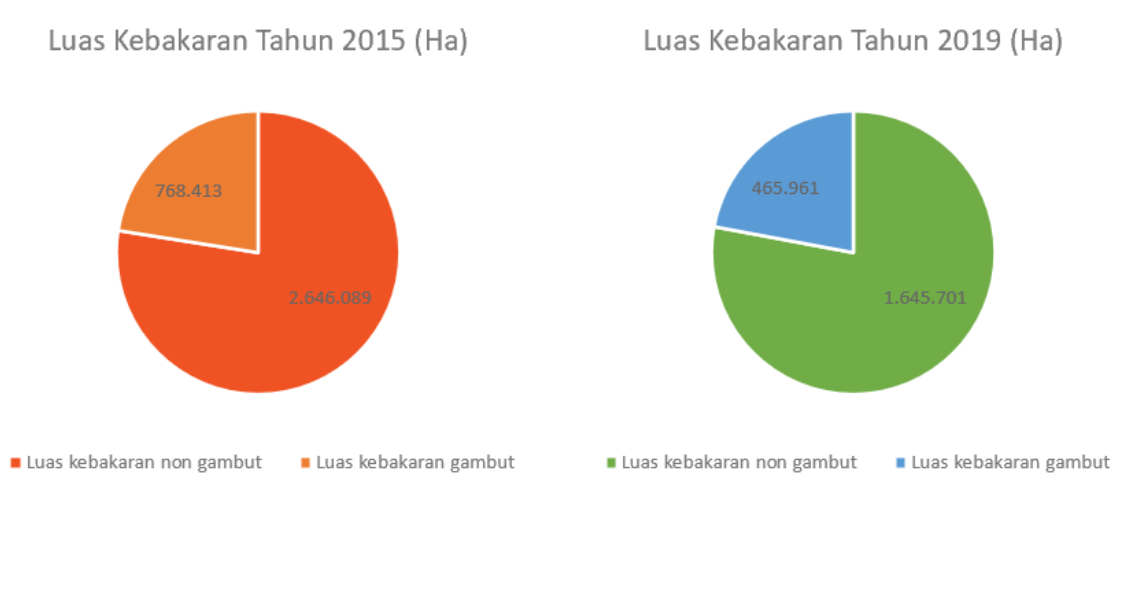

Looking at historical data on forest and land fires in Indonesia over a five-year period (2015 – 2019), the biggest fires occurred in 2015 and 2019 which burned around 2.6 million and 1.6 million hectares of forest and land in Indonesia. The two severe fires that occurred in that period of year were also worsened by prolonged dry season conditions and the El Niño that occurred in Indonesia. Around 29% from the two severe fires occurred on peatlands.

Even though the area of fires that occurred in peat areas was smaller than in non-peat areas, forest and land fires that occurred in these peat areas deserved more attention. The reason is because peat has a huge amount of carbon stored inside of it. When the peat is drained, which causes the peat to degrade, it can emit an average of 55 metric tons of CO2 each year. This figure is equivalent to burning more than six thousand gallons of gasoline. The KLHK stated that 83.4% of peat ecosystems in Indonesia were damaged and needed to be restored.

If peat drainage is continued with land clearing using fire, the emissions released from the peat burning process will be even greater and can accelerate global warming. Based on emission data released by the KLHK, the forestry sector is the largest emission producing sector in 2015 and 2019. The total emissions released from the forestry sector in 2015 reached 1.5 million Gg CO2 and in 2019 amounted to 923 thousand Gg CO2 in which these values were also contributed from forest and peatland fires.

Peat fires are also very difficult to extinguish, it even can take months. Fire that spreads in the deep layers of the peat which contains a lot of dry organic matter such as leaves, branches, tree trunks, becomes an effective fuel that keeps the fire burning beneath the surface of the peat even though the fire is no longer visible on the surface.

Areas Vulnerable to Burning Based on Land Cover Classification

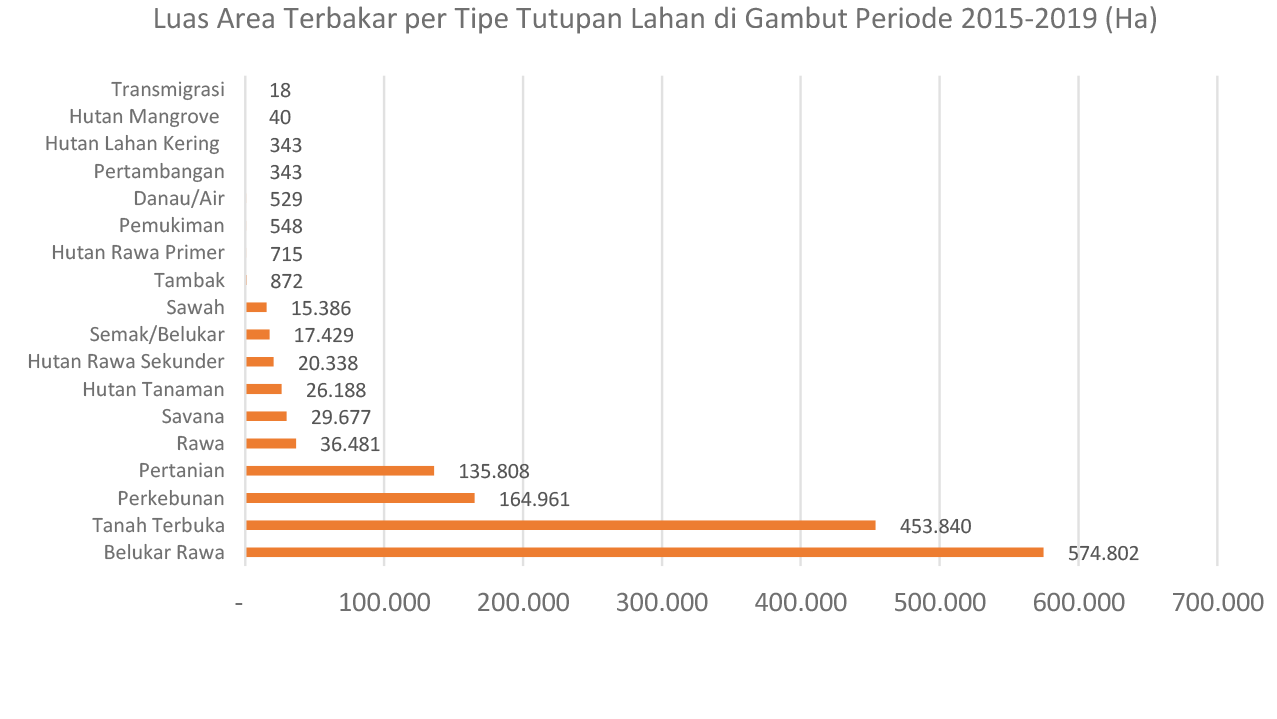

To monitor peat areas that are prone to fire, Pantau Gambut conducted a historical analysis of fires based on existing land cover on peatlands. The analysis of 2015 – 2019 data show that swamp thickets are areas with land cover that experience fires most often. During this period, around 574 thousand hectares of swamp scrub land cover has burned. Open land, plantations and agriculture are also types of land cover that are prone to fires in this five-year period with a total area of more than 100,000 hectares burned.

Peat Province Vulnerable to Burning

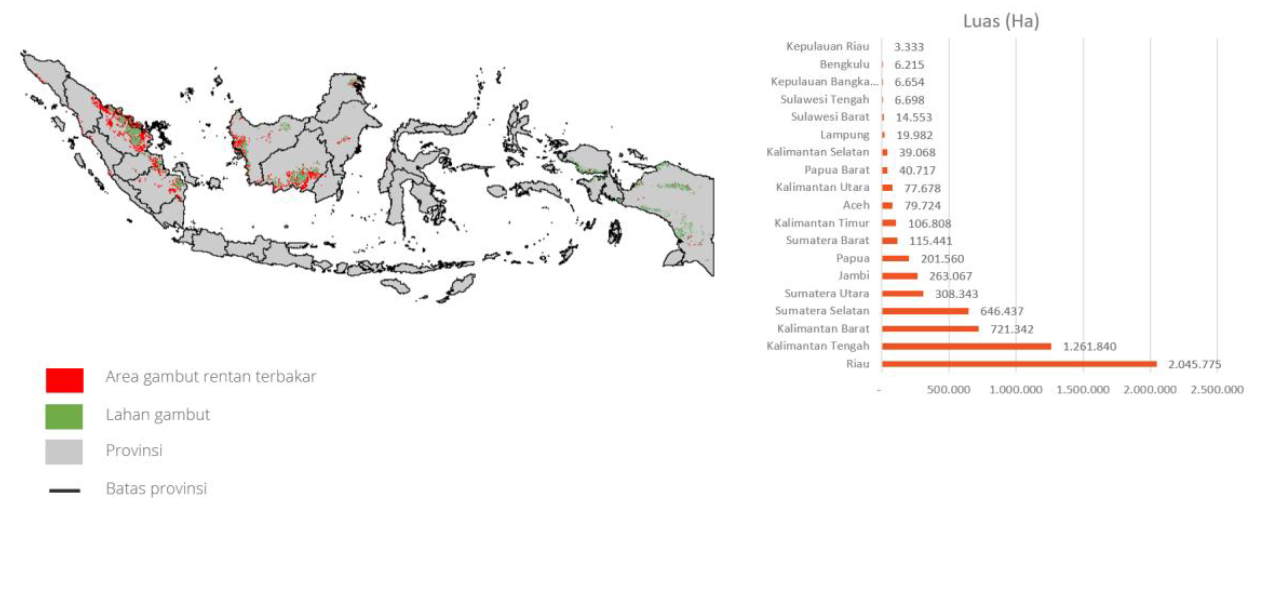

From the four land covers that are prone to fire, the results of the analysis show that the area that is most prone to fire is in Riau Province, with 2 million hectares of prone area, followed by Central Kalimantan, with a prone area of 1.2 million hectares. Pantau Gambut continues the analysis based on those areas in each province. Riau Province has the largest burn-prone area based on land cover of 2 million hectares, followed by Central Kalimantan with 1.2 million hectares.

More attention is needed for the Provinces of Riau and Central Kalimantan in terms of forest and land fires because these two provinces often experience peat fires every year. Based on the average results of data on peat fires owned by the KLHK in 2015 and 2019, 14% of the burned areas were in Riau Province, 36% were in Central Kalimantan Province, and the rest were scattered in other peat provinces.

Vulnerable Areas to Burning Based on Land Ownership

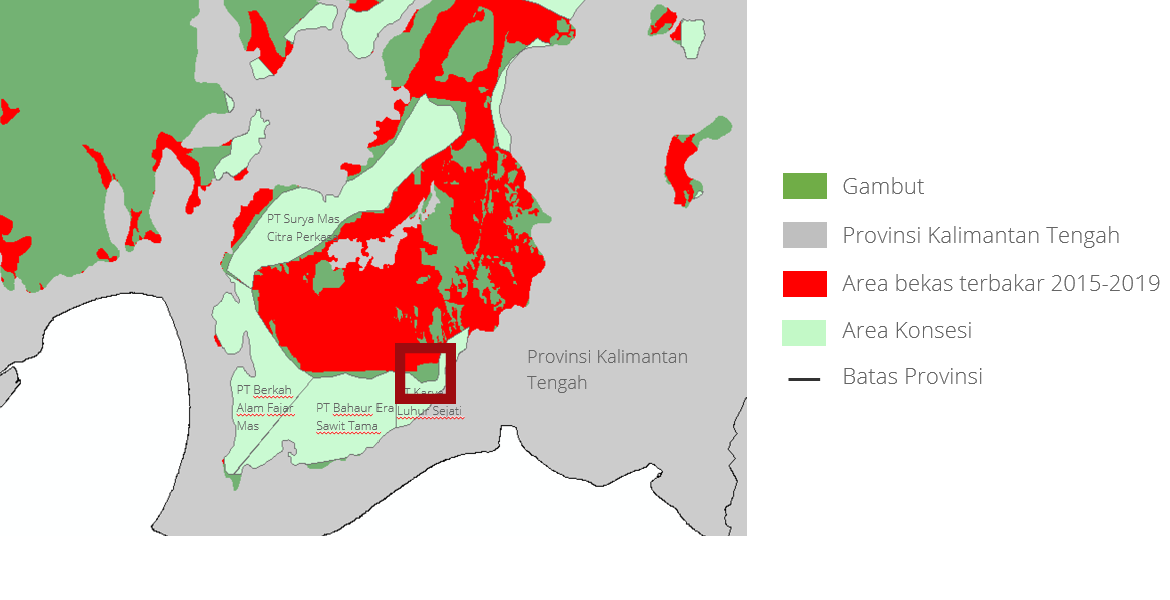

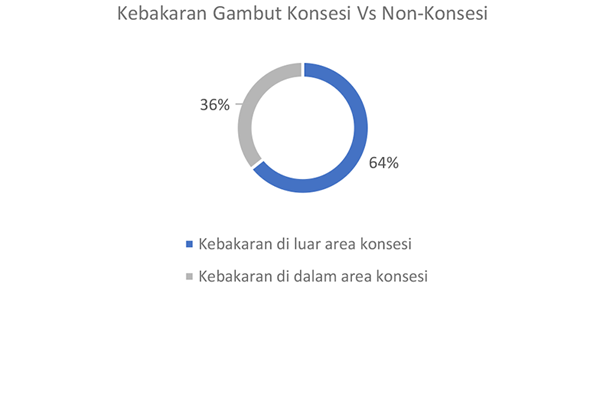

Based on the results of fire data analysis, the extent of fires occurring inside the concession area is still much smaller than that of fires inside concession area (Figure 5), but the concession area must still be a priority for monitoring. This is because from the results of field monitoring, it appears that the activities of utilizing protected peat area for extractive industry and burnt areas that have not been restored are instead replanted with oil palm and acacia plantations (Figure 6).

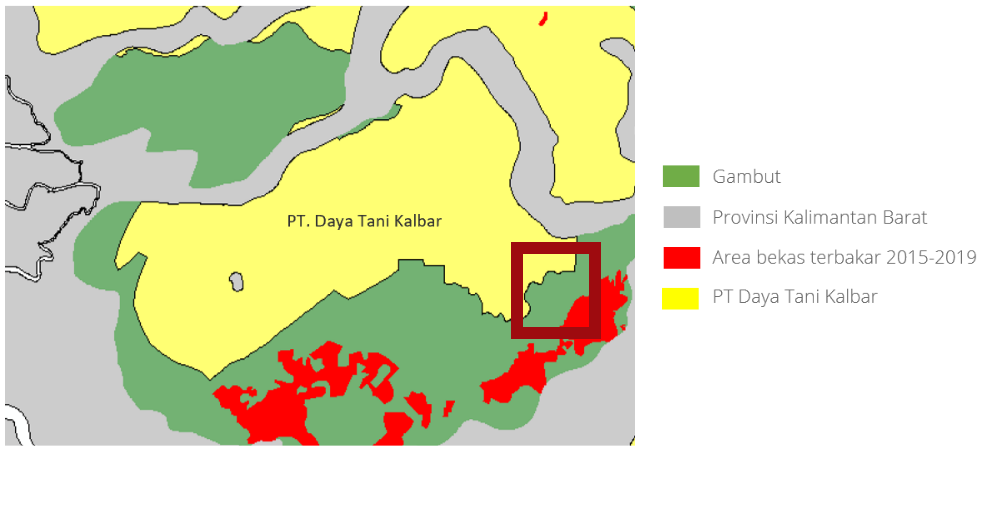

A deeper investigation of the fire areas that occurred in non-concession areas, which accounted for the largest proportion of peat burned areas, showed that 18.4% of fires were detected within a radius of one km from the outer boundary of the concession on peat. Verification results via satellite imagery show that the appearance of burnt land within a radius of one km has changed to form a structured and neat pattern of plantation areas (Figures 8, 9, 10). This pattern change raises the question; is this an activity that is deliberately carried out to expand the plantation area? With these data, it is necessary to increase supervision and alertness towards areas that are prone to fires so that forest and land fires can be prevented.

Central Kalimantan Province

Jambi Province

West Kalimantan Province

Read the complete Pantau Gambut report on "Beware of Vulnerability to Forest and Land Fires in 2022" as attached.