Hope After Eight Years…

By Budi KurniawanTo Keep Peatlands Wet

Last August, the author had the opportunity to see firsthand the closure of canals in the Padang Sugihan Wildlife Sanctuary using soil as the main media and paperbark. During the New Order era, Padang Sugihan was known as a place for migrants to live and farm. Recently, the area has been restored to its original function, including by rearranging the canals to maintain water supply in peatlands throughout the year.

It took about 90 minutes by speedboat to reach the location. From the pier on the murky edge of the Padang River, it took about 10 minutes by foot, crossing the bushes and grasslands.

When we got there, we saw a round lump resembling a sepak takraw ball in the corner of a canal. Not only one, but up to a dozen of the slightly dark green object were found. Later, I found out that it was elephant dung. Elephants still live freely in the Padang Sugihan Wildlife Sanctuary, Banyuasin, South Sumatra. Mammals from the elephantidae family and the proboscidea order still survive thanks to the variety of plants that become their main diet.

The location where we found the elephant dung was about a stone's throw away from one of the canals backfilled by the Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG).

The canals are backfilled to close the illegal loggers’ access and to protect areas consisting of swamps, peatlands, forests, and homes for various types of animals from fires in the dry season.

In 2015, about 63 thousand hectares of this area were damaged by fire. According to the Head of the Peatland Restoration Agency, Nazir Foead, canal backfilling is one way to maintain the peatlands’ level of wetness aside from the watering and water bombing methods.

BRG selected the canal backfilling method instead of blocking the canals because the width of the canals in the conservation area was more than 10 meters.

This backfilled canal was located at the coordinates of S2.925524 E105.10407. We saw that the canal closure could hold the water at the upstream part. The inundated water flowed and penetrated the soil on the left and right sides of the canal. Meanwhile, there was no water at all at the downstream part which leads to the Padang River.

Head of BRG, Nazir Foead, explained that the backfilling process has been ongoing since 2017 and the result is evident every dry season. The land around the canals remains moist and some of them are still inundated with water. Although it has not rained in this area for almost a month, which makes it very susceptible to fire, the canal closure has succeeded in maintaining the water level in swamps and peatlands.

There were at least 12 points of canal backfilling in the wildlife sanctuary. In addition to canal backfilling, BRG also drilled wells in areas far from water sources. The drilled wells are also used to water the trees in order to reforest the burned land. In this dry season, the trees still look green, fresh, and sprouting buds on some parts of the branches.

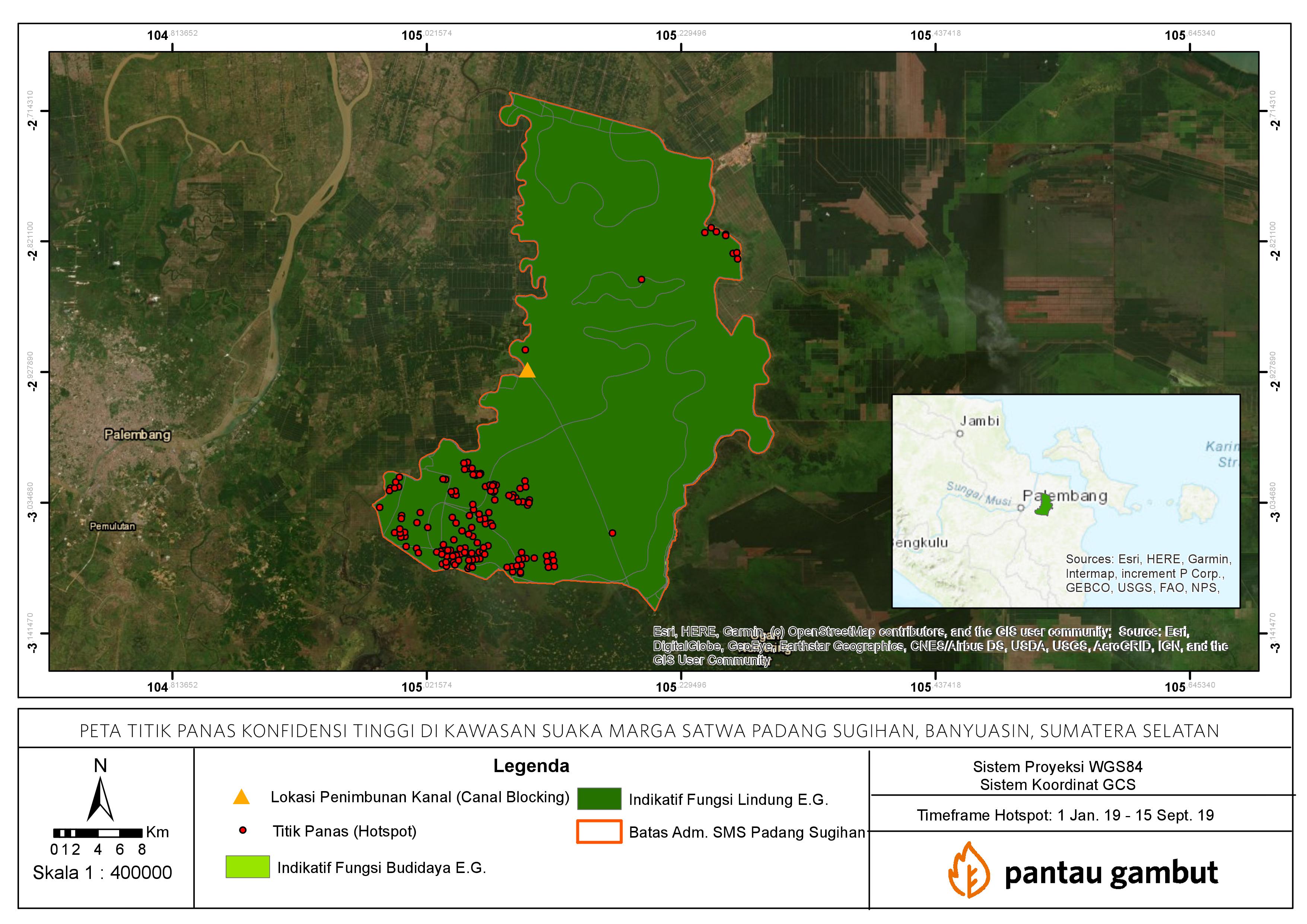

According to Nazir, canal backfilling was proven to be effective in maintaining the land’s level of wetness. So, even though it has been almost a month without rain, the area is still wet. From the result of overlaying the canal closure map with the hotspot map from January-September 2019, we can see that there is only 1 hotspot around the closure sites.

Padang Sugihan Wildlife Sanctuary is also known for its large herd of elephants that still live freely there. Based on data obtained from the manager of the Elephant Training Center, there are about 38 tame elephants and 50-60 wild elephants in the sanctuary, consisting of adult male and female elephants, calves, and even heavily pregnant elephants. Considering the massive land and forest fires in 2015, the same risk still threatens the lives of those elephants this year.

Dr. Ir. Muh. Bambang Prayitno, M.Agr.Sc., a lecturer at the Faculty of Agriculture of Sriwijaya University, knows most of the sanctuary area. He has visited the sanctuary for research and other purposes since the early 1990s. The last time he went there was in 2017 to see the impact of the fire that occurred two years earlier and to think about the measures the government should take to save the peat ecosystem.

Bambang recounted that the government opened the Padang Sugihan Wildlife Sanctuary for transmigrant area in the early 1980s. The construction of canals was intended to drain the land so that people can settle and farm there. Unfortunately, this was done without an in-depth study so that it has damaged the peat ecosystem. The area around the canals becomes dry and very prone to fire during the dry season. The canals also make it easier for people to enter the area.

“The government should have thought about the vegetation and food supply for the animals that live there. They should have closed the canals quickly but apparently they did not do that so anyone could enter the area,” said Bambang.

“Now we can’t even see paperbark there, let alone trees with more expensive woods. The peatland is almost gone too, there are only some spots left,” he added. For this reason, he strongly supports the closure of canals in the sanctuary so that water won’t flow to the Saleh River, Padang River, and Sugihan River. Moreover, canal backfilling can maintain the water level so that it can wet the area around the canals. After successfully maintaining the wetness of the land, the next step is to revegetate the area.

Based on various researches and studies on peat ecosystem, Bambang Prayitno recommends to maintain the function of primary and secondary forests as much as possible, including in South Sumatra. As for the damaged area, he recommends to immediately enhance the function and make improvements to the land around the peat forest by rewetting, revegetation, and revitalization. "Assist the farmers, for example by planting paperbark trees to help them improve their economy."

Onesimus Patiung, head of the South Sumatra sub-working group, explained that BRG had conducted an in-depth study before filling the canal. They had considered many factors beforehand. In some places, efforts to protect peat ecosystems were opposed by the community. In some cases, the residents even tried to reopen the canals because their rice fields became dry during the canal closure.

The canal backfilling process has started in early 2017. 10 sites were backfilled in 2017, 18 sites in 2018, and 9 sites will be backfilled this year. “Canal backfilling is intended to improve the peat ecosystem in Padang Sugihan Wildlife Sanctuary," said Onesimus.

The implementation of restoration activities refers to the condition of areas burned in 2015. To date, around 47 thousand hectares of peatlands have been directly affected by the canal closures. Originally, the construction of canals was intended to drain peatlands. As a result, the area becomes very prone to fire during the dry season. "If the peatland is wet again, hopefully the peat ecosystem will be restored to its original condition before the canals were built," he added.