Recurring Forest and Land Fires, a Bad Reflection on the Peat Protection Effort

By Hairul SobriSonor Tradition, Between Changes in Landscape and Regulation

Since decades ago, people have been growing food crops in Lebak Rawang. There are at least 60 families who cultivate the peat swamp. "Our parents have been planting rice on that land since the 1960s," said Sukri, who is also the Head of Makmur Sejahtera Farmers Group, to Pantau Gambut, on Friday, 24 September 2021.

Now, the residents of Jerambah Rengas Village can’t plant rice anymore. They are used to the sonor tradition or burning to clear the land for small-scale agriculture. Sukri said that without burning, it will cost a lot to clear agricultural land. "The burning method is commonly used by the people when we enter the planting season," he said.

Government Regulation Number 57 of 2016 has forbidden the traditional system. The regulation is an amendment to Government Regulation No. 71 of 2014 which also prohibits people from burning peatlands.

"It’s better to be preventive. The costs will be much more expensive if a fire has occurred," said Iskandar, Head of Ogan Komering Ilir District.

The people are not wrong in wanting to maintain the sonor tradition because sonor is the only practice applied by the local people to cultivate food crops on peatlands. However, changes in the landscape due to the conversion of peatlands make this method no longer relevant. In 2014, the Agricultural Research and Development Agency noted that around 3.74 million hectares out of the 14.9 million hectares of peatlands had been degraded. The degradation process begins with forest conversion into extractive industry and mining concessions. Land-use change has drained the peatland, making it prone to fire.

Scientific evidence shows that burning land is not appropriate for peat ecosystems. Based on a study by the World Resources Institute (WRI) Indonesia, burning peatlands will reduce the nutrients needed for plant growth. Burning land will damage the peatland’s ability to absorb and store water. It also accelerates land subsidence, causing the land to be easily flooded during the rainy season.

Peat ecosystem in traditional knowledge

If there is no introduction of other methods for sustainable agricultural practices, the residents of Jerambah Rengas Village will have difficulty in meeting their food needs. The regulation needs to be followed with the introduction of new cultivation methods that support sustainable use of peatlands, so that the existing regulations will not be detrimental to the local community.

Anthropologist from the University of Indonesia, Suraya Abdulwahab Afiff, explained that traditional systems are based on the knowledge that prioritizes sustainability, including timing in farming, farming methods, selecting plants based on land conditions, and understanding the seasons. If that knowledge is replaced, it will be very risky for the local community. "The old tradition maintains a good ecosystem," he said.

As for the traditional system of burning land, Suraya referred to his research in Central Kalimantan in 2017. If we want communities that uphold tradition to change their traditional ways, then they need to understand the new system to reap real benefits. “Is there any guarantee of success using the new method? How do people get food if it fails?” he said questioningly.

Suraya understands that it is not easy when people want to change the traditional system. "They need to be guided, so that they can really get through the problems and reap the benefits," he said.

If a change is needed, we must consider its affordability, whether it can be accepted by the community to meet their food needs. "We must prepare a solution when we issue a new policy," he said.

When the government formulates policies, they should also prepare alternatives that can guarantee the people's welfare, so that the regulations can support the sustainability of peat ecosystem without harming the community’s food supply. Suraya explained that the peat ecosystem, which was originally in harmony with nature, was often disturbed by concession activities. "When big capital comes in, there will be a gap in the ownership of production land," he said.

On the east coast of South Sumatra (Ogan Komering Ilir and Banyuasin), most of the people are farmers or fishermen. They grow rice not to earn money, but to provide food on their tables. People who cultivate rice will also work as fishermen or rubber farmers to earn an income. If they are free to cultivate the land, then they can grow various types of vegetables or fruits as alternatives, such as watermelon, pineapple, pumpkin, papaya, long beans, and chili.

“If they can grow their own food, they don’t need to spend money to buy it. And they can save their income from fishing or working as rubber farmers,” said Dhio Dhanni Shineba, Secretary of Perkumpulan Tanah Air, a non-governmental organization in South Sumatra.

They have a custom that prohibits them from selling their rice because they view rice as the spirit of life. "If they have abundant yields, they will give the rice to other people who need it," said Hasbi, 64, a community leader from Jerambah Rengas Village.

Rice production is seen as a tradition to achieve food security. "Basically, this custom is a model for local food sovereignty," said Syahroni, an agroecologist based in Lebak Rawang.

History of fires in Lebak Rawang

It is inappropriate to blame the people's traditional system of burning land for the fires in Lebak Rawang. Lebak Rawang's landscape has changed since concession companies began to operate there. These changes have caused the peatlands to be prone to fire, especially since some areas are bordering with the oil palm plantations. This is a different situation compared to when their ancestors introduced the sonor tradition.

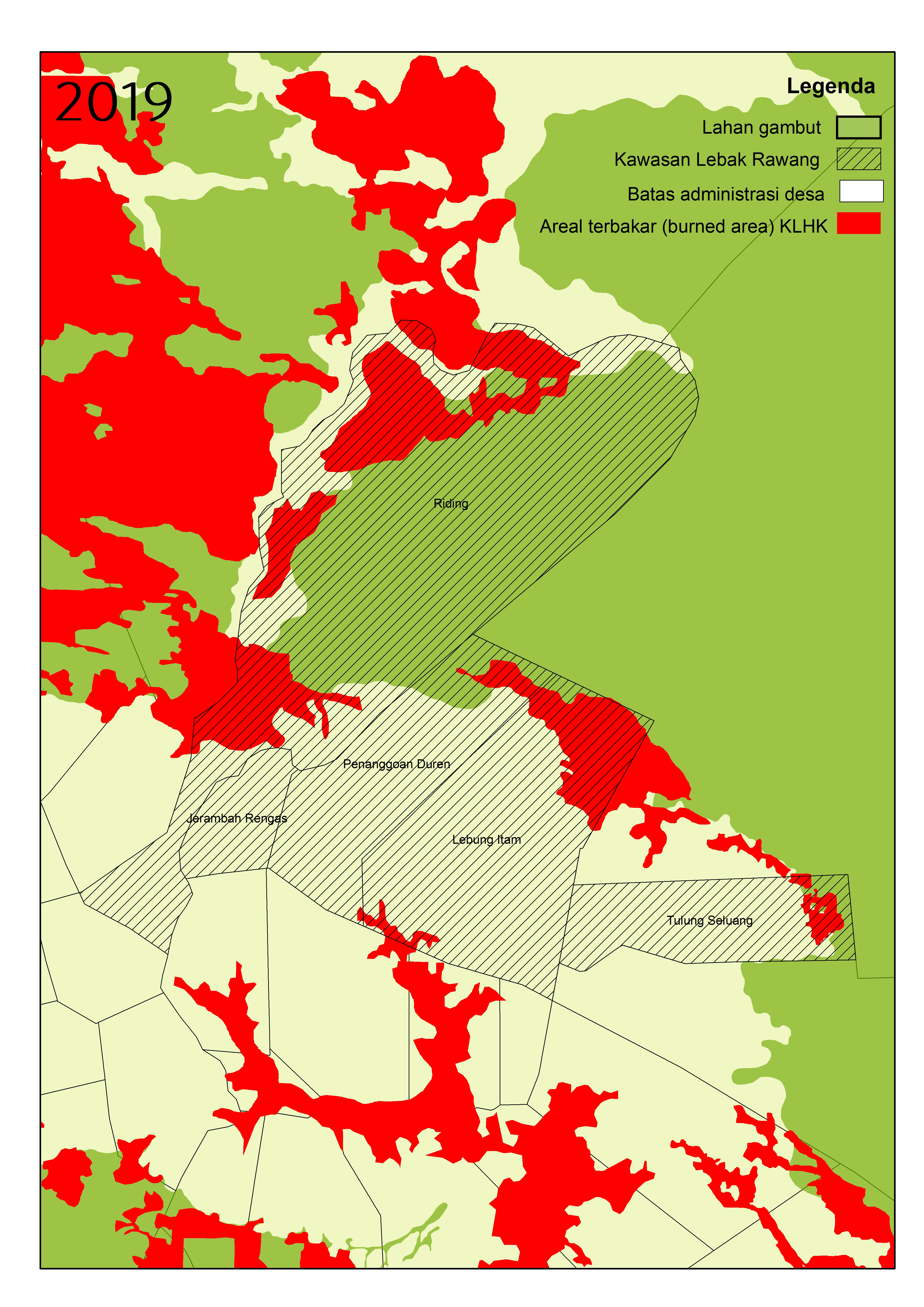

Lebak Rawang area includes five villages, i.e. Jerambah Rengas, Riding, Penanggoan Duren, Lebung Itam, Tulung Seluang. Pantau Gambut observed that Lebak Rawang had a history of fires every year from 2015 to 2019. The biggest fire occurred in 2015, burning 19,292 hectares of land. Then there was no fire at all for two years. In 2018, another fire occurred, burning 251 hectares of land. In 2019, the fire burned 5,895 hectares of land.

The area is threatened by fires every year. Head of the Center for Climate Change and Land and Forest Fires Control (PPIKHL) for Sumatra Region, Ferdian Krisnanto, considers community empowerment as an important approach, which prioritizes the value of education and humanism to create a positive impact. "There are various problems. We have to understand the reasons why people burning the land," he said.

Actually, the reason is obviously to clear agricultural land. "But the impact of the fire is much bigger," he said.