Saving the Muaro Jambi Peat Orchid

By Yitno SupraptoMaking Money from Jambi's Coastal Peatland

The sounds of paddling broke the silence of the creek that divides Sungai Beras Village, Mendahara Ulu Sub-District, East Tanjung Jabung District, Jambi Province. Among the thick nipa nipah branches (Nypa fruticans) that grow wildly along the river, Marwiyah swung her machete to slash the nipah fronds that are starting to wither. The machete moved wildly, slashing the nipah fronds one by one, then slowly piling it up in the canoe.

In the East Tanjung Jabung coastal area, nipah trees thrive without requiring human intervention. The plants that support the peat area also functions as a habitat for wildlife along the Mendahara River and its river branches, as well as a source of livelihood for the surrounding community.

During the day, Marwiyah can collect dozens of nipah fronds, which she cuts into one-meter long pieces. The fronds are split up and then left to dry in the sun before finally being burned to turn them into an ingredient for making salt.

Since 2018, after returning from training in a food art school in Javara Indonesia, Jakarta, which was facilitated by the Peat Restoration Agency (BRG), the housewives started making salt from nipa nipah fronds to fulfill her customers' orders.

To make one kilogram of nipah salt, Marwiyah needs almost 100 kilograms of wet nipah fronds. However, this is not a problem because nipa nipah trees thrive along the river in the East Tanjung Jabung coastal area. She only needs to take a few fronds from the bottom part of the nipah tree, which contains the most salt.

"I've counted that 28 kilograms of wet fronds, only 5 kilograms would remain after drying, and after burning will only yield three ounces of salt," said Marwiyah.

The 51-year-old woman began explaining the steps of making salt from nipah fronds. “The wet fronds are dried in the sun, I cut them into small pieces to make them dry quickly. After it's dry, I will burn them and wet the ashes so they will be clean when I filter them. After that, I’ll just boil them until they’re dry and collect the salt from the crusts.”

It takes 5-7 days to turn the nipah fronds into salt. "If it’s sunny, the process could be fast, but if it’s rainy like it is now, the process can take a long time, as the frond doesn't dry out," said Marwiyah.

The price of nipah salt, which is quite expensive, can support the family's economy whilst the economy is affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. One kilogram of nipah salt could be worth up to Rp 500,000. The price is relatively expensive compared to sea salt.

However, Marwiyah still has difficulty marketing the nipah salt to the public because of the relatively high price. "People think, why would I buy expensive salt, if I buy ordinary salt, I can get a lot of salt. They don't understand the health benefits."

At the moment she is only selling nipah salt to Javara Indonesia. Marwiyah has started supplying nipah salt to Javara in 2018, but it was halted due to price issues. Now the business relationship has continued. She even plans to invite the Sungai Beras PKK women's group in working together to produce nipah salt, if demand from Javara Indonesia continues to increase. "Javara ordered 5 kilograms of salt this month, if the demand increases, I can also invite PKK women to work together," she said.

Kholik's wife also said that nipah salt contains antioxidants and is safe to be consumed by people with stroke and hypertension. She got this information by participating in training at Javara Indonesia.

Asmadi Saad, an agrotechnology lecturer at the University of Jambi, said that nipah salt has more complex elements compared to sea salt because it’s made from organic materials.

“Nipah salt contains iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and potassium (K), due to its organic ingredients. Sea salt tends to contain NaCl (sodium chloride) because the production process requires it to be dried out into crystals," said Asmadi.

However, the lecturer who is also a member of the Peat Restoration Agency's expert group has not been able to confirm if the nipah salt is indeed safe for consumption by people with hypertension or who have experienced a stroke.

"No research has been able to prove this. Maybe this is what we need to research further,” said Asmadi.

There aren’t many nipah salt producers in Indonesia, especially in Papua. Jambi is rich in nipah trees and also started producing nipah salt after Marwiyah attended the training in Javara Indonesia. The lack of nipah salt production has limited the supply to the market, thus making the price quite high.

Rispa, Head of Industry at the Industry and Trade Office of East Tanjung Jabung District, admitted that he always supports the potential in his province. "We will always give our support we encourage development, as long as it has the potential to improve the community's economy and the local wisdom," he said.

“We help with the promotion and marketing. We (the government) have built a souvenir shop, so these products can be sold there," added Rispa.

In his opinion, the problem that they are currently facing is that the community has not been able to consistently produce. “Sometimes they produce, but sometimes they don’t. We are also confused on how to promote it, but when there is an event we ask them to produce so we can promote it at the exhibition.”

The Sungai Beras community is actually already familiar with salt made of nipah fronds since several decades ago. However, their production process is different as they do not burn the nipah frond, instead, the wet nipah fronds are ground to extract its water. The water is then boiled to produce salt.

“Back then, the Tuo Kito people also made salt from nipah, because no sea salt was available. Now, a lot of sea salt is sold at a cheap price so I don't use salt made of nipah anymore," said Hamid, the Head of Sungai Beras Hamlet.

In addition to the frond, which can be processed into salt, young nipah fruit can also be processed into juice. "To make it slightly sweeter, you can add palm sugar, hence it’s all organic and healthier."

While the half-ripe fruit can be processed into dodol. Marwiyah has proven that the nipah dodol is as delicious as coconut dodol. Processed nipah was able to win third place in the food processing competition at the Jambi Province some time ago.

"If the fruit is overripe, it can be made into flour to make cakes. I've tried it, it’s delicious when used to make cookies”.

In creative hands, overripe and damaged nipah can be used as craft materials to make souvenirs. "Some are made into dolls, others are turned into key chains," said Rispa.

The annual tourism event held by the East Tanjung Jabung Government is the right time to promote these community-based products. For example, thousands of people gather in the Kampung Laut Festival in April - August and various culinary specialties from the coast are offered. The Safar Bathing tradition, which falls every Safar month in the Hijri calendar is also able to attract thousands of visitors.

The Threat of Forest and Land Fires

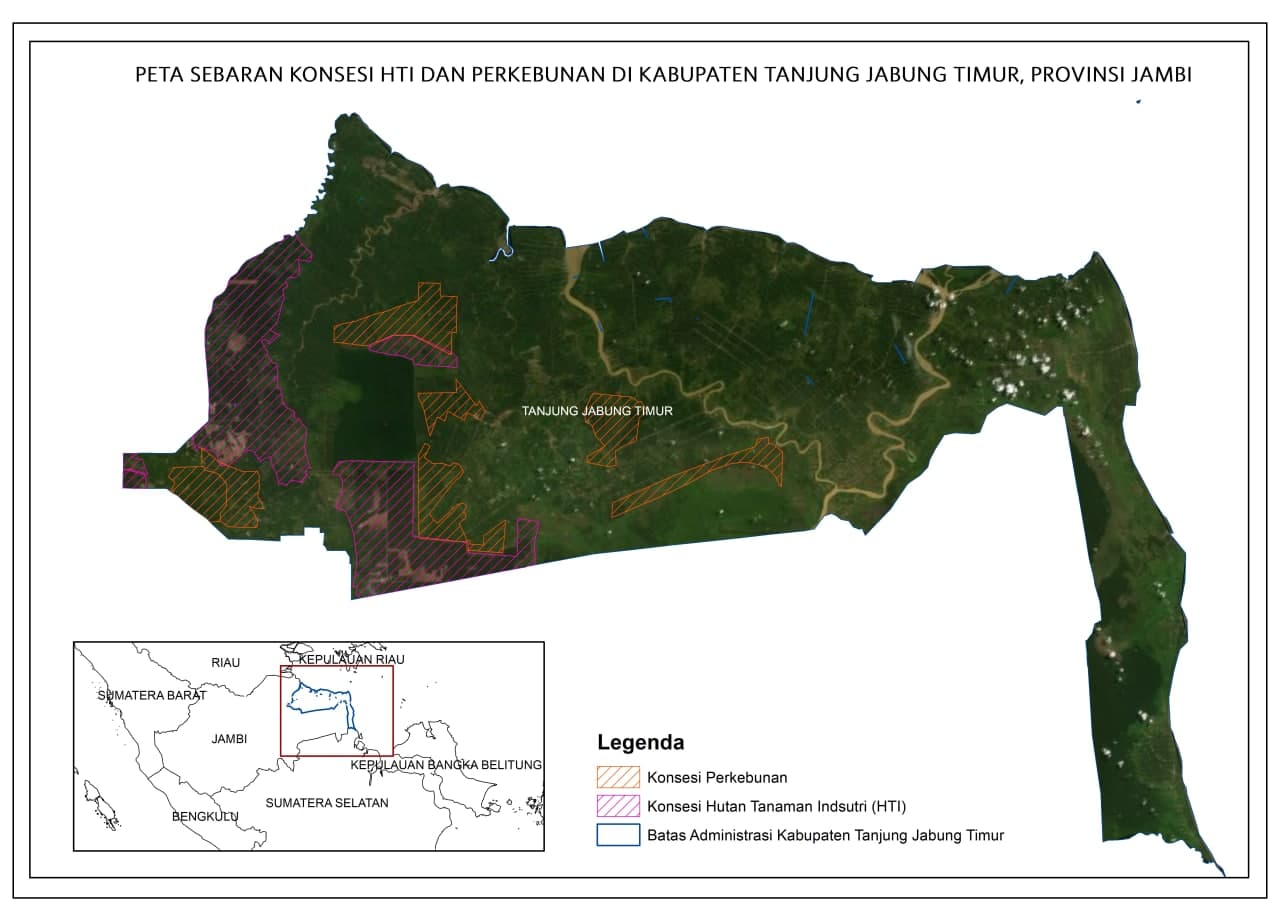

Fires and exploitation of peatlands in East Tanjung Jabung have also eroded the nipah tree habitat that once thrived on the river banks. The majority of the total 181,000 hectares of peatland has been controlled by plantation companies and industrial plantation forests (HTI). Most of the peat is damaged and will eventually trigger repeated fires.

Peat damage due to fires not only damages the environment, but also the surrounding community. The habitat is damaged, food supply is disrupted, and public health is also threatened.

The land fires that occurred in the East Tanjung Jabung area in 2007 forced the Sungai Beras Village community to learn the many ways of cultivating peatlands. They strictly maintain the water level to keep the peatlands safe from fire. This was proven when Sungai Beras Village successfully survived the 2015 and 2019 fires.

“The Sungai Beras community has these strict rules—maintaining the water levels—not to recklessly cultivate the peatlands. They managed to keep the peat wet to avoid catastrophic fires,” said Sukma Reni, Coordinator of KKI Warsi’s Communications Division.

The people of Sungai Beras also slowly began to apply agroforestry patterns in an effort to sustainably manage their plantations. Approximately 67 hectares of areca and coconut plantations are cultivated using the intercropping method with coffee. Some of the oil palm plantations were also discontinued and replaced with liberica coffee alongside swamp jelutung, which is more peat-friendly.

"There are 4 hectares of a coffee plantation that the farmers have started to cultivate," said Habibi Mainas, peat community, and district facilitator.

Keeping the peat wet not only prevents catastrophic fires but also saves the peat ecosystems from degradation.

In fact, the Sungai Beras community has secured their crop-producing land by implementing a peat-friendly agroforestry cropping pattern. This sustainable practice should be a valuable lesson for people from other regions that are managing peatlands. The lesson is that they should also take ecological aspects into consideration in meeting their economic needs to minimize the adverse impacts of forest and land fires.

.jpg)